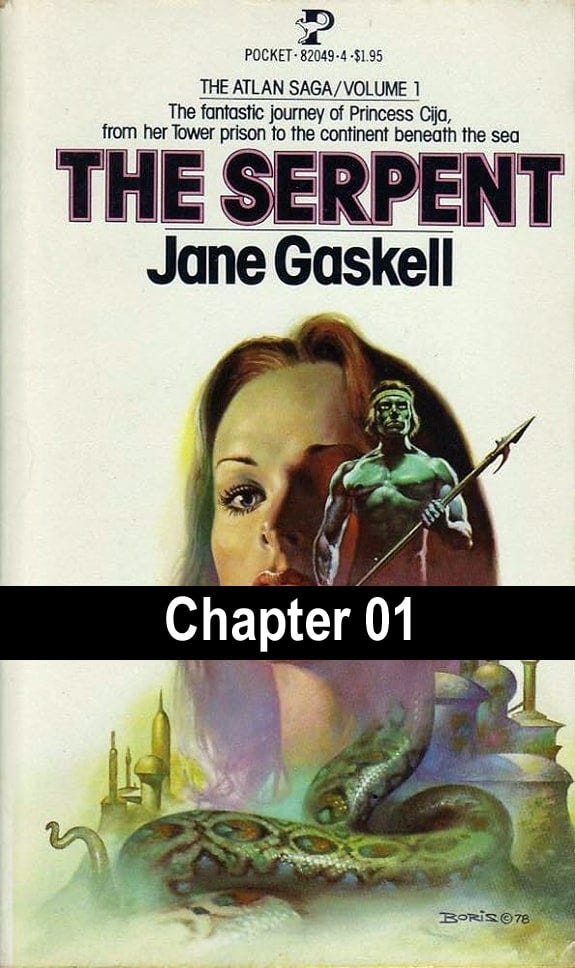

The Serpent by Jane Gaskell - Chapter 1 (Part of)

1963 Genre: Vintage Paperback / Sword and Sorcery

THE SERPENT, the first installment of Jane Gaskell's ATLAN saga, we meet Cija, on unlikely young princess-heroine who has been imprisoned in a tower all her life. She was placed there for safe-keeping since from her birth she carries a curse and is doomed to betray her country. When her mother, the chief goddess of the land releases her, it is only as a hostage to Zerd, the half-man, half-serpent lord of a conquering army. But not before assigning her a secret task. She must seduce Zerd, and once alone with him, kill him: No small order for a maid of 17, who was, until recently, ignorant of the very existence of male humans.

Cija goes off with Zerd who is on his way to attempt a greater conquest—the fabled Continent of Atlan. The journey releases upon Cija a series of adventures that ore so different and startlingly original from normal fantasy fore that it is all we can do to hang on to our seats. But somehow we do, as Cija is alternately; goddess-princess-heroine of thousands, the mistress of a large-bird-creature she rides along on her journey, camp follower, scullion, footman, empress, slave, cook and yes, possibly a great warrior. This thrilling tole is sure to win Jane Gaskell the accolade of being one of the finest writers of fantasy in this generation.

Chapter 1 (Part of)

THE TOWER

I can't see things so well from any other window.

The nearest mountain, a huge hazy turquoise-green thing, conical, terrible, is so near I can see the thickly-forested ridges and the blue precipices and the grey chasms. The mountain behind that, and separated from it by the sea, is less evenly shaped and on clear days looks as though it's going to lurch forward. It is fascinating but ominous. The third mountain, between and beyond them, is so distant that even on clear days I can't make out more than a vague pattern of changing shades, valleys and slopes, floating in the insubstantial horizon.

And beyond the horizon lie the Northern lands, where the terror-legends come from. My own nurses used to scare and horrify me with tales of how I would be given to the cruel barbarous animal-people there, if I were not good. The people there are animals, they are not descended from the gods as we are. There is no kindness, no mercy, pity or gentleness possible to their natures. They are avaricious and savage; at best they are callous, at their worst they are sadistic and no atrocity is beyond giving them pleasure.

Physically they are brutish, graceless. So it is exciting to look out over the sea and mountains and know that they enclose me from the Northern lands, secure, safe in the benediction of our ancestors the gods, in our own prosperity and beauty.

And the sea is nearer to see from this window than any other in the tower. It would be gorgeous to watch it during storms except that then it is mostly hidden from me by the huge swift continuous sweeps of rain.

The tumbled stones lying round the ruined window-way were of a great heat when I first ventured to touch them.

One rocked, hesitated, plunged and fell into the abyss.

I leaned over as far as I dared and watched its awful drop.

It left an unfamiliar space on the sill. That really was a day on which there was a happening. I was shaking all the time but I got up slowly, steadied myself, climbed on to the broad sill, and walked over the unsteady tumbled ancient stones on it until I had nearly come to the edge. I lowered myself with slow, slow care to stooping and then looked down for the first time on what is below.

It was wonderful; I felt like a poet and an explorer in one daring creamy skin.

I was so enthralled I almost forgot how dangerous my position was on the edge of the sill.

The first time was wonderful and the others have really been just as wonderful but also more conscious of the danger.

There is a small round plateau down there. It is grassy in its centre and rocky round the edges and a little thin blue thing shone through it. And from my reading, I knew at once that I must be beholding a stream.

I gazed down at this new unguessed of scene and all the time the corner of my eye was aware of a white glint. I craned round till my neck was horribly ricked and, my hands gripping violently at a bit of protruding wall, I saw a piece of a white stone building.

Unblinking, my eyes widened.

At least, I expect they did, they have to anyway for this type of happening, according to most of the prose I've read.

I hung, silently, gazing at new horizons.

The white building whose end I was seeing obviously began somewhere quite beyond my range of vision. I thought (just at first) it might be a bit of this tower but I didn't recognise it.

It's a stone terrace, open to the sun, behind a beautifully-worked stone balustrade which looks tiny from this distance, and behind is a flat-roofed hall into whose shady clean blue colonnades I can see for some way before it disappears into its own shadows.

It all looks so cool, and unattainable.

I wondered and wondered.

Was it part of my own tower? But no, I had explored it from corner to corner since babyhood. (I know far more about it even than they do.)

'It must be the end terrace of my mother's palace,' I thought.

Then I twisted myself back till my whole weight rested on the hot broad sill again. I clambered back over the uneasy stones and lowered myself into the secure little Passage beyond.

I would ask my mother some questions next time.

So I did, and she evaded them and questioned me instead and I had to be very clever and evade her questions because I don't want anyone to find out about the Passage. But I am sure, by now, that that is the end of my mother's palace and that I have seen part of the outside World.

On the third day of every single week, every week might be permissible but always the third day, they put long revolting aprons over their trousers and scrub the floors. If they think I have been particularly bad, they make me help them and I have been helping them for months now with only one week off.

The whole point of my starting this diary is that I am utterly fed-up and I must work off my steam somehow and a good way to do it is to write it all down, so I shall.

Actually I wouldn't care if Glurbia got hold of it and read just what I think of her, and all the others but particularly Glurbia, but I am writing it in my private code and to keep it even more to myself I am keeping it in the Passage. At the rate of present progress (ha ha!) I may have to use this Diary as a safety valve for years and years, but luckily it is a huge book made even bigger really by the fact that it has thin pages which are a nuisance to write on but gives me more pages. It is one of Glurbia's account-books which should have lasted her for the next five years but she's had to get another one because this one has disappeared. As far as she's concerned it has anyway. But she thinks she must have mislaid it because if I had taken it what would I have used it for? Well, we shall see.

I have made a place for it at the end of the Passage. Have hidden it, together with this sticky-tipped deep black scriber which I have attached to the lock of the book, together with the dear little key, by a long tape—have hidden it under some stones (which make it rather dusty but never mind).

And I have made a vow to be just as rambling and infantile as I feel like being because what else is a secret Diary for if not to be a recipient of all one's feelings?

Of course, some people can record happenings in their Diaries, if my books are to be believed, but what hope have I of that?

Their legs are thick and blue-white and when they pull up their trousers, nearly to the knee, so they can kneel easier, this is blatantly visible.

Not only are the legs repulsive but it almost makes me sick to have to look at them.

And poor little me, my own legs are of course longer and slenderer and a much more aesthetic shape but it wasn't very nice to have to know that my legs were just as blue-white.

Whenever the colour of the legs of the women in the books are mentioned they are 'beautiful gold-brown legs'. And I yearned for them. But I can't even get a little satisfaction like that, oh no. Glurbia caught me lying beside the fountain in the sun, with my trousers off.

'Cija !' the dear old lady gasped and went such a charming shade of magenta. 'You wicked, wicked girl! Oh, you wicked—put your clothes back on at once. How dare you act in such a way? What would your mother say? You sinful, shameful girl!'

'I want to get brown,' I said.

Mild enough. No need at all for all the nagging that went on solidly for weeks afterwards, and it's still always being mentioned.

Haven't breathed to Glurbia that I'd read of the women with brown legs. So she thought it was an original idea on my part—'original sin'. But if I reminded anyone of the existence of those books they'd be removed from the bookroom.

At least, whenever I can, I sneak away to this window-niche at the end of the Passage.

And here, where the sun pours in past the mountains, I remove my clothes. I am now a beautiful creamy colour. Surfaces like my shins are a crisp gold-like well-done fry. Places with a little almost-fold, like where my breast meets my armpits, or my tummy meets my groin, are pale gold. Veins still show blue though. From here, I can just hear the sound of their voices as they call, 'Cija! Cija!' If they want me for some very annoying task, or if I am in a very daring mood, I just sit quiet and don't answer them.

They never search for me here.

I don't think they ever even knew of the entrance to the Passage behind the old wall-hangings.

They are very stupid.

The daily quarrel is over for today (unless it's a more-than-one-quarrel-day).

I had been here and ignored their squeals, 'Cija, Cija, Cija,' etc., etc., etc.

Then at meal-time, 'Cija,' said Glurbia, 'where have you been?'

'Oh, nowhere.'

'You are defiant and impudent,' said Snedde. 'Lately, Cija, you seem to be forgetting all the care and affection with which we have laboured to make you into a lovely and well-bred girl.' Not because I was stricken by remorse at the stark truth of Snedde's words but because it is rather a shame to upset the old imbecile, I quickly kissed her cheek. Snedde's moustache prickles. I withdrew myself from Snedde's answering embrace, trying wearily to stifle the distaste I know I am wicked and ungrateful to feel.

'Here is your bread,' Rorla said, handing over a plate.

I took the plate, not even mentioning the charming cracks across it in which mould is growing. If I had mentioned it Rorla would be in for it from Glurbia for giving me the plate, because Rorla cracked it and is supposed to use it until the supplies come, including extra plates. I hope they come soon.

So then I asked as carelessly as possible, 'When is my mother's next visit?'

'Your mother is coming tomorrow, so the floors must be polished.'

'Again?'

'I don't like your tone,' Glurbia said, using her cold voice.

'I wouldn't mind so much if the floors were dirty,' I said reasonably. 'But they are no less clean now than they will be when we've polished them.'

'Your opinion as to cleanliness is not that of conscientious persons, Cija. And it's quite disgusting of you to moan whenever you have to set your hands to a little work. Other girls of your age have many more hardships to suffer.' In a couple of long cold sarcastic sentences she can make me hate her. In fact, I hate them all nearly all the time now.

All right, all right, so I'm selfish and lazy and never think of anyone but myself. ( Incidentally, that's surely permissible when I'm the only interesting person about?) However, that seems to be me and I prefer it to changing to them so I shall stay selfish and lazy.

So just now I said, 'Other girls of my age aren't treated the way I am—they meet people—' and then I stopped.

I know, really, that that one is going too far.

I suppose it is unkind, it is disobedient and immodest of me to talk in that way.

Only because I am so special ( though not too special to scrub floors) am I allowed to reside in this finely-laid-out and comfortable castle, with a dozen women to look after me—if not actually at my beck and call. I am different from other people, my blood is unique. I am treated with great care, have been since I was born, because I'm more than the equal of any piece of precious fragile porcelain.

But I shrugged my shoulders.

'What breaks my heart,' I said bitterly, more to be disagreeable than because I think it true because I know a lot of it is my fault, 'is that you all used to be so nice and talk to me and read to me and play with me before you suddenly started to scold me all the time!' I turned my back on them and walked across to the fountain.

It hurts to know you've hurt someone as close to you as they are, but there's a sad sort of sour joy in hurting anyone.

I slipped my feet from my sandals and into the fresh cool spray.

'My darling child,' Glurbia's sober voice said, and I don't think she was hurt and I don't think she was loving me, she was just ticking me off ( they never, never never, never, do anything else), 'what you fail to realise is that you have, in the last year, become intractable and moody and you can't bear to be told when you are wrong, even though you must know that you are.'

'I'm sick and tired of being scolded,' I remarked and began to splash my feet. 'You treat me like a baby. I've been alive for seventeen years.'

'You may have larger breasts and hips than you had a few years ago, but in other ways you are still a child and under our guard and guidance. You didn't resent our authority when you were eight, why should you now? And you will be under it for a long time to come. You are not yet old enough for us to become your maids; we are your nurses and have every right to expect obedience and gratitude—at least respect.' I jumped up.

'That's what I can't bear!' I yelled as loud as I could.

'That's the thing driving me mad! I'm to be stuck here with you how many years till I can see the World and new faces and become real? I'd like to commit suicide, often, I'm so bored and I only feel alive, my mind gets thrown back from its live sections because it has nothing but this all the time.'

'Cija—'

'You tell me I'm precious, but what's the good in it for me?' I snatched up my last piece of bread and honey, flung it angrily and wastefully into the fountain, and ran into the room leaving them hurt and angry and offended and worried.

By the time they had followed me I was here, inside my hidden Passage.

Hiccuping slightly, I walked through the cobwebbed darkness.

It makes me more angry, perhaps, than anything else does to realise that all the endless advice they're always giving me about running about during meals is quite correct.

It does give one hiccups.

The nurses bowed their heads down as far as they could, which was not very far because their rheumatism was bad again today, and my mother walked slowly between them.

She came to me, put out her hands, so that all her armlets and rings clanged together, and placed them on my shoulders.

'What a lovely dress, Cija darling. Who made it?'

'Cija made it herself,' Glurbia said with pride.

'Indeed? You are teaching her well.'

'They helped me a lot with it,' I said sullenly. I didn't want to take all the responsibility for the dreadful thing.

'And has she been good since my last visit?'

'Quite good, Dictatress.' My mother smiled, the women filed past her, and the little courtyard was empty but for Cija and her parent who sat down beside the fountain, and of course but for the slaves who stood holding the Dictatress' train clear from the pavement.

'What sunny weather we are having.'

'Yes, Mother.' It seemed to me my mother was preoccupied.

She was smiling vaguely round at the sky and the sunlit stone and the silky-looking sea far below the parapet, plucking with the fingers of one hand at the gigantic onyx ring on the hand which so maternally held mine.

I said one or two half-witted things, like—'I'm glad the extra plates have come' and 'Snedde's turtle is rather frisky, it may be going to have eggs, don't you think?' and then I ventured, 'Are you thinking of anything, Mother?' The Dictatress turned, looked at me, and smiled less vaguely.

'I was thinking of some business which is worrying me in the world outside,' she said. 'But, see, Cija, I have a present for you.'

'A present?' I echoed and the Dictatress clapped her hands.

One of the slaves holding her train came forward and immediately another slave deftly took the vacated corner of the train.

'Bring Ooldra,' said the Dictatress.

The slave's diaphanous trousers belled m the wind her speed created as she rushed out of sight.

'What is the present, Mother?' I inquired.

But the Dicta tress had become vague again.

'The present is that which we should always enjoy lest we die tomorrow,' she murmured.

'There is no need for you to quote things at me, Mother,' I said crossly. 'I get enough of that all the rest of the time.'

'Poor Cija. And how fluffy your hair is, child. Has it just been washed? You should sleek it with that grease—you know—the brown grease—'

'I know the grease. It's brown and it also stinks.

Well, have you no perfume with which to scent your head afterwards?'

'I am not allowed to use perfume—'

'Oh, Cija, quick, look up there, up there, dear—see those delicious little pink birds chasing each other across the roof?'

'How sweet. Mother, I'm not allowed to use perfume. Can't you speak to them about it?'

'Ah, here is Ooldra. Give me the package, Ooldra, the one for little Cija.' Half eager, half annoyed, I raised my eyes and met Ooldra's.

Ooldra smiled.

'Now here is the package, Cija.' The Dictatress' square (not like mine) fingers plucked at the seal. 'Look, Cija dear, a lovely necklace. Let me fit it round your neck.'

'Oh,' I breathed, at least I think I did.

Even the slaves bent forward to look.

There was a glitter of white stones and I felt their hard cold against my throat. I closed my eyes.

Someone screamed.

I opened my eyes, heard the necklace clatter to the pavement, saw the terror on the faces of the slaves, saw my mother snatch a lash from her wide belt and unmercifully beat a slave.

'My train! You have let my train slip and touch the ground!' Realising what had happened, I moaned with fear.

The other slave, holding both ends of the train, quivered as if there were a high wind.

'For the first time in two thousand years the Train of the Dictator has touched the ground!' The sky had grown dark and it began to rain.

Great drops of rain hit my forehead.

The slave, appalled by the omen her accident had brought, did no more than wail in soft agony under the brutality of my mother's whip.

The third slave stepped back and her bare foot crunched on my necklace.

Thunder spanned the sky in one leap.

It was too dark to see anything now, but even above the rain and thunder the whipping could be heard.

Ooldra laughed.

I folded into its seventeen intricate folds the dress Glurbia insisted on my making for myself and placed it neatly on my clothes-shelf.

The little room was dark. I'm never allowed candles after twilight.

I determinedly laid myself on my bed. 'I will sleep now. I won't think of it anymore.

'Oh, but it is terrible.

'It is terrible.

'It is terrible.' The phrase kept going over and over in my head. I was tired, too tired to be, any longer, really terrified. I am still tired but somehow excited and my writing has gone all big and scrawly even though at every third sentence or so I start to try to control it.

The omen has occurred, it is the most terrible thing I could ever have known to happen; for the first time in two thousand years the Train of the Dictator has touched the ground.

A wind, gusting quite suddenly through the window, sucked the coverlet from my body.

I sat upright at once and stared and stared in superstitious suspicion at the window. I wonder if anything is safe anymore.

Heavy raindrops spattered through.

I slid out of bed and went to fasten the shutters. But that would've made it so still and warm in the room.

I would be quite unable to sleep, yet anyway.

The room beyond is unfamiliar in darkness. No matter what shape any piece of furniture is, it looks exactly as if it has just gathered itself together to jump on you. They are all lawless at night and only sleep bars you from that nightliness.

The door behind the curtain doesn't creak, it is used so often now. This Passage has come to mean Security to me.

Please let us know if you like this story in the comments. If there is enough interest, we will publish more of this story.

Another great series that I'd be VERY happy to see get an eBook rerelease.