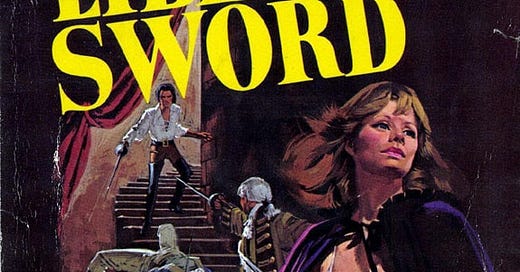

The Liberty Sword by Gardner F Fox - Chapter 01

1976 Genre: Historical Fiction / American Revolution

A Swashbuckling Tale of the American Revolution.

DO or DIE!

This is a tale of epic proportions, its action spanning two continents. The Liberty Sword follows the struggles of Benjamin Franklin and his first “spies” as they seek to turn the tide of the revolution against the British.

Action, intrigue, and romance are set against the backdrop of the greatest revolution in the world in this rich and powerful novel.

Chapter 01

Philadelphia

Autumn, 1776

A chill October wind swept dry leaves rustling up Spruce Street as I came out of the Bull Tavern, wrapping my great cloak closer about my chest. Jamaica rum was warm in my middle, making a gentle fire along my veins. Under my arm I carried the lacquer case which held my two rapiers.

I am a master of fence in this city of Philadelphia, and had just been attending the two sons of Bemus Parks in an upstairs room, attempting to teach them the finer points of riposte and remise. I fear they will be but poor swordsmen; they lack the agility, the fire and imagination of the true duelist; but then, dueling is much out of style in this new world.

I bent my tricorne hat to the wind, relishing its push against my legs, my flapping coat. A bag of Pine Tree shillings weighted down my greatcoat pocket, payment for me labors. The rum had been an added bonus, three beakers of it, thick and oily, good to the insides in this fall of the year. Ahead lay my rooms above the long chamber on Market Street that was my salle.

There would be sausages to fry and a length of crisp bread, home-baked by my pretty landlady, Denise Pettibone, together with a platter of turnips and greens. And, if I played my cards right, a glass or two of wine with my landlady herself. And perhaps, afterward, she would yield to my caresses and share my big, empty bed above-stairs.

Life was pleasant and serene for me, these days. Oh, yes, there was trouble in the colonies, there had been an uprising in Boston, an army had been formed under a Virginia landowner named Washington, some battles had been fought. But I had held myself aloof from that. I was of no mind to go marching off with a musket in my hands, to die perhaps on some wilderness battlefield.

I lacked for little in the way of worldly pleasure. My salle made money for me, I ate well enough and lived the kind of life I wanted. I had high hopes, too, of inducing my landlady to carry her flirtatious ways to their proper conclusion on some raw winter evening.

How is a man to know when he walks toward destiny?

I moved along Spruce Street past Holy Trinity Church and the cemetery beyond it. It was an old, familiar way to me. The houses are of red brick and white stone, with gabled roofs and clean, neatly tended doorways. The streets were dark, except for the few iron lanterns hanging from the brick walls siding the front doors. I walked in the splashes of light these lanterns made, avoiding the piles of slop, the horse ordure.

I shifted the carrying case from my left arm to my right. Only another block or two and I would be home in my rooms, smelling the sausages and, I trusted, the faint perfume of petite Denise Pettibone.

The clank of metal on stone made me lift my head.

My right hand held the tricorne more closely to my head as I lowered the rapier case. I stood motionless against the wind. The night was silent. The sound was not repeated.

Strangely, the fact disquieted me.

I am swordsman enough to know the tools of my trade. It was a small-sword that had made that sound, brushing against a brick wall. But who in Philadelphia would walk its cobbled streets with a naked sword in his hand?

I shrugged. This sound in the night was no concern of mine. A man who puts his nose where it is not wanted usually gets it pinched. I walked on, but I went more carefully, walking with the toes of my boots, much in the manner of the Delaware or Susquehanna Indians who occasionally came into Philadelphia with furs to trade."

As I neared Apprentice Alley, which is a small cross-way between Eighth Street and Chestnut, I ran my gaze along its cobblestones.

Two men stood at the far end of the alley, their backs against the bricks. Each held a small-sword in hand, bared to the night air. Obviously, they waited for someone. Intent on their task, they paid me no heed as I moved quietly into the alleyway shadows.

As silently, I undid the snap of my carrying case and placing it on the ground, drew out one of my rapiers.

I could have wished for a better blade in case of trouble. These lengths of steel were never made for grim fighting, only for the art of fence. Their tips were blunted, as were their edges. I would have felt safer with the Ferrara blade that hung on my salle wall, for instance, or one of the English swords newly come from London town.

In a well of dark shadow, I stood motionless, my cloak wrapped about the blade to hide its glittering length from the chance reflection of a lantern hanging a few feet away.

Nor had I long to wait.

For heavy footsteps came up Chestnut Street, moving slowly, ponderously, almost as a scholar might walk. I could make out the tap-tapping of a cane, as well. One of the men at the far end of the alley gestured with an impatient hand, and they pushed further back against the wall. Slowly I began my walk, placing my jackboots as silently as I could.

The alley was perhaps sixty feet long. I was fifteen feet from the two men when I saw their victim on the other side of Chestnut Street.

He was an older man, rather corpulent, with a fur cap on his head and clad in plain clothes that made him look something like a Quaker. A tradesman? A merchant on his way home from his counting-house? Were these men setting out to rob him of his profit?

No matter what their motive.

I smiled grimly, clutched the rapier more tightly.

The two men moved so suddenly they were halfway across the cobbles before I could call out.

“Gentlemen,” I shouted, running forward.

The heavy-set man with the glasses perched on the end of his nose had paused at the sudden appearance of the swordsmen. He turned to stare as I raced from the alleyway. There was no fear in him; at least, none that I could see. He wore no wig, but a thick great-cloak did its best to hide his ample middle, and square-toed walking shoes with pewter buckles adorned his feet.

A tradesman, obviously. "

The two men swung around from their victim to face me. I slid out of my coat, exposing the rapier. One of the men laughed harshly and waved a hand at me.

“Take the fool, Harry. I'll finish off Franklin.”

I did not wait for the attack. I was on them before he finished speaking, turning for a moment to parry the small-sword the man named Harry thrust at me.

I caught his blade in a circular bind and whipped it sideways. Then I went after the second and smaller ruffler, catching him by the shoulder and, sinking fingers into cloak and waistcoat, hurled him sideways and off balance.

To their staring victim I called, "Put your back to the nearest door, if you'll be so good. The door is recessed. They cannot come at you without getting past my blade.”

Obediently, the man did as I asked. I stationed myself before him, back to his front, and waited, blade out and held low, in tierce.

The two men glanced at one another, then at me.

“It makes the killing a little more difficult, this interruption, but not impossible,” said one.

They came together, thrusting at the same time. I beat against one blade, parried the other. I gave myself over to my enjoyment of the moment, thinking of the youths to whom I was trying to teach this art of fence, of their clumsiness and lack of coordination.

For once, there was no need to hold back my flying point. These were street rufflers, assassins, despite the finery of their satin coats and breeches, their silk stockings and powdered wigs. I am not a conceited man, but fencing is my occupation, my life's work. I make my living at it. I would be a dullard indeed, if I did not regard myself as a fine swordsman.

For a few seconds the constant tac tac of the blades occupied all my attention. The first onrush of your duelist is the most dangerous. You are ignorant of his method of attack, of his defense.

But after a few moments, the true swordsman can discover a weakness in his opponent. The man to my left was bigger and heavier than his companion; heavy jowls gave him a porcine look. He was slow, he would tire more easily than his companion. Already my rapier was knocking his point further and further away at every beat.

The second man was smaller and more wiry. He would be the more dangerous opponent.

And so I set myself to concentrate on the smaller man, pausing almost contemptuously from time to time to parry the blade of the heavier man, then appearing to forget him as I carried on my thrust and parry with the other.

My lack of caution emboldened him, as I had hoped. He noted my preoccupation with his companion, my seeing indifference to his presence.

He came stamping in, thrusting hard.

My blade touched his, fell away in a faint and riposted. I aimed high, for his face. The tip of the rapier was dull, but it would destroy an eye, properly placed.

My rapier scratched across his eyeball.

The man screamed and dropped back, letting his sword fall as he clapped both hands to his face.

"I've been blinded, Jamie. Blinded!”

It was done so suddenly that the smaller man had no chance to move forward before the deed was done. His every sense had been attuned to the rapid thrust and parry in which our blades were engaged. For that brief instant it had taken to riposte and lunge at his opponent, he was flatfooted.

I whirled, lunging.

My opponent skipped back, cursing.

The big man was staggering off, still with his hands across his bleeding face. His companion stared at him wildly, then looked at me. His rat's face was twisted into a grotesque mask of hate and baffled fury.

“Lord God," he breathed, and came at me.

His blade whipped snakelike in the dim light of the iron lantern a few feet away. This little man was a good sworder, but he was no maitre d'armes. My parries carried his point to one side of me and the other.

My ripostes became swift stabs that sent him skipping backward. He gave way slowly, fighting fiercely, moving back foot by foot across the cobbles.

By this time windows were being opened and night-capped heads were thrusting out. A lamp or two began to glow, giving us more light by which to fight.

Voices rose in indignation. There were parts of Philadelphia where such an altercation might cause no comment, but this was a fine residential district. Soon men would come running from their houses.

The little man sensed this. His eyes darted from house to house. The fury that had held him in its spell gave way to caution.

He snarled, “We'll meet again, my fine bucko. You'll pay for Harry's eye when we do.”

He whirled and ran after his companion, and in a moment they were out of sight along a nearby alleyway. I might have gone after him—my blood was up—but the man behind me laid his hand on my shoulder, staying me.

“Let them go,” he said quietly. “They are not worth the trouble.”

He came down off the doorstep, smiling faintly, walking with that heavy tread that made him seem so ponderous. Behind his glasses, his eyes were bright and shrewd as they looked at me. In this first moment of our acquaintance, he struck me as a man who cared little for outward, external appearances.

With his fingertips he scratched his head under the fur cap. He seemed very much the pedant, somewhat absent-minded and perhaps overmuch given to philosophizing.

"I—ah—am somewhat at a loss for words,” he smiled. “I have never had the occasion to thank anyone for saving my life.”

I laughed, and placing the tip of my rapier between two cobblestones, thrust it into the dirt. As I wiped off the dirt with a corner of my greatcoat, I said, “Allow me to thank you for the opportunity of engaging in a real fight, instead of the mock duels I wage daily with my pupils.”

I made a leg to him. “My name is David Mercer. I conduct a salle d'armes not far from here, on Market Street.”

His bushy eyebrows raised. “That explains your marvelous swordsmanship. I've never seen better, and I have watched men fence in London many times. You're to be complimented, sir.”

By this time we had been surrounded, as men in various stages of dress and undress crowded in around us. Bare heads and bewigged heads nodded and whispered in the night; there were shoulders covered by greatcoats, by cloaks, that shivered under the light wrapping of a waistcoat.

A man pushed his way through the crowd, a small bag dangling from his hand. His eyes went to my companion, then looked hard at me.

"There's a fleck or two or blood on the stones,” he said. “Is either of you hurt?”

"Neither of us, thanks to my friend's ability with that blade he holds.” The heavy-set man smiled at me, waving at the newcomer. "Doctor Edwards, let me present David Mercer, my rescuer. My young Hector, this is Doctor Mortimer Edwards. My own name is Franklin, Benjamin Franklin.”

I am afraid I gawked. There was no proper Philadelphian who did not know the famous Doctor Franklin. His fame and his exploits were on everyone's tongue. I myself had copies of his Poor Richard's Almanack on my night table, together with his Pennsylvania Gazette. There was talk, too, of his having discovered that lightning was something called electricity. He had discovered this by means of a kite and a key, though what useful purpose this might serve was beyond me.

Still, my face froze in mingled disbelief and delight.

The physician laughed good-naturedly. “You hit better than you aimed, sir. All Philadelphia—Nay, all our colonies are in your debt.”

Franklin smiled wryly. “It seems I underestimated the strength of the British spy system. It's a mistake I'll not make again.”

I bowed, smiling at Benjamin Franklin and the others. “Fate has made me its servant, sir. I thank you for the exercise. I hope to serve you as well another time. But now, if you'll excuse me, I'm on my way home to a late supper.”

I left him rubbing his jowls and looking after me with a curious regard. My heart was singing as I moved down Apprentice Alley with my rapier case thrust under my arm. Benjamin Franklin, Benjamin Franklin, a voice whispered inside me. One of the most influential men in all the thirteen colonies.

I could not help but profit from this chance meeting, as a result of this night's dueling. The sons of many good burghers would beat deep paths to my door, to learn the art of self-defense with small-swords. My salle would ring with the voices of the well-to-do. My money bags would bulge with the fees they paid.

I walked along Market Street with a high heart. All any young man needed was an opportunity, a chance to prove his worth. Tonight, my own moment had come adventuring. In the days and weeks to come, I would reap my reward for a task well done.

A shudder touched me as I reflected what might have happened, had I not seen those two men lurking in the alleyway.

As I neared my lodging, I noted that Denise Pettibone had lighted the oil boats, for their rays shone through the heavy window-draperies. Good Denise! Pretty Denise! She was as fine a cook as she was a seamstress, but it was neither her fine capons nor the satin dresses she made for herself that held my thoughts, but rather her dimpled shoulders exposed in the low-necked gowns she wore, and the brightness of her black eyes.

Of late I have been contemplating marriage with Denise Pettibone. I have taken to mooning over her as I lie in my lonely bed of nights, as I walk the streets, even, upon occasion, as I face a pupil across our dueling rapiers. Until now, I have felt I had little to offer, beyond myself.

Whereas she owned the house in which I had my salle and my bedroom, two more houses over on Arch Street which she rented out to merchants and their families, and was the possessor of a fine farm in the Southwark section of the city. She was a young widow, as I had been given to understand, and perhaps eager for a second husband.

My fortune would be made, were I to believe the hints and innuendos she never tired of letting fall, by marriage with her. As her husband, according to our law, all her properties would be my own. The salle d'armes need not be my sole means of livelihood.

Why, then, did I hesitate?

I would hesitate no longer. This very night I would ask for her hand. We would be married, spend our honeymoon in my bedroom, and I would be a rich man. My encounter with Benjamin Franklin had put a fever of expectation in my blood.

I inserted my iron key in the lock and threw open the door. Denise Pettibone was there in the hallway, staring at me with wide eyes.

Her face was a mask of terror.

“Oh,” she whispered. “It's—you.”

“Of course," I smiled, troubled by the fear that stared out of those brilliant eyes, contorting her lovely face. “Who else would it be?”

I moved toward her, caught her cold hands in mine and held them to my chest. Up this close, I was struck again by her beauty. Her eyes were large, brilliant, shadowed by long black lashes in which tears brimmed, threatening to spill over. The mouth that quivered so pitifully was wide, very red, and looked succulent as a berry.

Normally her face was possessed of an elfin, mischievous pertness that made me gape at her like any schoolboy smitten with love for the first time. Now it was filled with fear, white and ashen.

“What's frightened you?” I asked gently.

“My—my husband. I saw him earlier, outside the house."

“Your husband? But I thought—”

She shook her head as if angry at herself. “I told you I was a widow, David. I believed I was a widow. I had been told that—my husband was dead.”

She drew her hands from my clasp and turned away. She was not a tall woman, the top of her head came to a little above my heart. At that instant I wanted to fold her in my arms, tell her that I would protect her from all the world, that from now on, her fears were my fears.

As I moved to do so, she struck away my hands. “It cannot be, don't you understand?”

I turned away from her then, hung my greatcoat and tricorne hat on the wooden pegs of the rack in the hallway. The mirror showed my lean face, rather dark from sunshine and the blood of my French father, with brown hair naturally curling and thick, close-cropped as was the fashion.

I possess broad shoulders, a lean waist, the long arms of your true swordsman. I am of something better than average height, and with the flush of my recent success heightening my appearance, I considered myself rather a fine figure of a man.

Apparently Denise Pettibone did not, however.

She was glowering at me, lips pouting almost petulantly.

"This changes everything between us,” she muttered.

“You were mistaken. You only thought you saw this man who was your husband. He is dead, you've told me so yourself.”

She shook her head, making her thick black hair tumble from its pins. A lock dropped beside her cheek, half hiding one of her eyes.

“I was told he was dead. I—I never saw his body.”

“Tomorrow I will go hunting the streets for this husband of yours. When I find him I will provoke a quarrel. I will kill him with my sword. It is that simple.”

"Bah! You are deluding yourself. No man is better with a sword than Christian Rivarol.”

“Christian Rivarol? Is this your husband's name?”

She nodded, her face sad and troubled. "He is a very bad man. I did not know how bad when I—I eloped with him, some years ago, when I was very young."

“You're upset," I murmured, moving toward her. “You had a chance glimpse through a window of a man who seemed to resemble your dead husband, nothing more. Now, come. Put a smile on those pretty lips.”

She sighed, lifted her eyes to mine. She was wearing a peach satin gown, ornate with ribbons and lace, that carried in its folds the disturbing scent of fine perfume. Her mouth was touched with scarlet salve and there was a beauty mark pasted to her suddenly dimpling cheek.

“Dear David,” she breathed. “You have the power to make me forget everything but the moment.”

She swept into a low curtsy, permitting my gaze to feast on the swells of her pale breasts nestling in the thin tissue of her fichu. My tongue became dry and clove to the roof of my mouth.

I could not control myself. Too long had I caught these glimpses of her loveliness, too often had I restrained my male impulses in the past. I stepped forward, caught her in my arms and brought her body close against my own.

A thunderous knocking sounded on the front door.

The terror was back in her eyes as she broke free of me and stared at my face. Her cheeks were ashen with the fright that made her tremble. This Christian Rivarol must be the very devil of a man to terrify her so, I reflected.

The knocking resumed.

I moved toward the front door and flung it open, half expecting some inhuman monster to fling itself at me. Instead I saw a middle-aged man, very decently clad in a Lindsey-woolsey coat and breeches, with cotton stockings and buckled shoes.

“David Mercer? Have I the honor of addressing him?”

I nodded, motioning him to step inside. To this he shook his head, saying, “I have not the time. I come from Benjamin Franklin. He desires speech with you. Now. Tonight. I'm to take you there as fast as possible.”

Denise was at my elbow, breathing fitfully. I said, "I'm sorry. I cannot leave here."

To my surprise, her voice urged, “You must go, David. It may be important."

I would have argued, but her eyes told me that she wanted me very much to leave. Perhaps she wanted time to think, to reflect on her fears of her suddenly-resurrected husband. Hope surged within me.

If she could convince herself that what I said was the truth, that she was the widow lady I had thought her, I might still win her affections. I nodded slowly, reached for my greatcoat and tricorne hat.

A carriage stood in the street, two horses tossing their heads and champing at their bits impatiently. I mounted up beside the middle-aged man who was the driver. Instantly the horses were in motion and we rattled off down Merchant Street.

Soon the carriage drew up to a large, roomy mansion in a court off High Street. Candles were lighted, their golden radiance in the windows fashioned golden haloes on the cobblestones outside. I swung down, waited for my companion, and was soon admitted into a room filled with musical instruments. I saw a viol-de-gamba, a Welsh harp, and an arrangement of glasses on a spindle called an armonica, which Franklin was credited with inventing.

A heavy tread turned my eyes from the armonica to the inventor himself. Franklin had discarded his fur cap and great-cloak, though his glasses still perched upon the tip of his nose.

“My young Hector.” He smiled, and extended his hand.

“You do me great honor, Doctor Franklin.”

He smiled, moving his hand to indicate I should be seated. He put his hands behind his back, clasped them, and regarded me with his cool gaze.

"How is it, sir, that you are not serving with General Washington and his armed forces? You are not a Tory, surely?”

“No, doctor. I am neither a Tory nor a patriot. My father was a Frenchman—our name originally was du Mercier—and my mother was from upper New Hampshire.” I shrugged and spread my hands. “I consider this to be a quarrel between Englishmen.”

A faint smile touched his wide lips. “As it is, no doubt, in the eyes of the world. But it is something more than that.” He seated himself in a blue wing chair and leaned forward, tapping me on the knee.

“We are no longer Englishmen or Frenchmen, David. Ever since early July, when representatives from all the thirteen colonies met to sign our Declaration of Independence, we are Americans. We are a new breed, David.”

His words, for some strange reason, made the blood surge quickly through my veins. I sat up straighter in the chair. I sensed his inner excitement, that transmitted itself to me.

“We believe in liberty, in the equality of men, David. There are no dukes or barons here, no noble class. It is a new concept. One man is as good as another.”

He frowned, staring off across the room. “Naturally, at this point in time, all our beliefs are in a somewhat precarious position. If the English defeat us, all our hopes and dreams will come tumbling down about our ears.

“This is why every man must give us what help he can.” His eyes twinkled as they met mine. “Even you, David. Perhaps—most especially you.”

"I can shoot a musket, yes,” I said dubiously. “I am not as good with one as I am with a sword. Still—”.

Franklin lifted a hand, palm toward me. “I am grateful that you are as you are, sir. I have a need for you.”

When I stared, dumbfounded, he chuckled. He grew sober immediately, however. “Why do you think that attack was made on me this evening? To prevent me from going to France. Yes, yes, to France, to petition for help against their old enemies, the English. Silas Deane is already in France, but he seems to be unable to accomplish what we want."

"I'm no statesman, doctor."

“Yet you can use a sword very creditably, and it comes to my mind that such a service may tip the scales in favor of the American cause. Let me explain.

“Secret documents from Deane have alerted us to the fact that British spies are working in France as well as here. Those Frenchmen who come out in favor of help against the English are attacked and taunted into duels, so that much of our support is fading.

"A swordsman would prove invaluable to me in France. As a bodyguard, yes. Perhaps as a secret agent, even more.”

He sat back, both hands on his thighs, and regarded me through his glasses. “Well, my young Hector? Would you be willing to sail to France with me within a day or two? To serve your country and your fellow men?”

I did not know what to tell him. All I could think of was Denise Pettibone. I could not bear to leave her in Philadelphia, to face the possible threat of a newly-risen husband.

He saw my indecision, and a strange sadness touched his rather coarse features. His grizzled head shook, and he sighed.

“I might promise you some pay, of course. Very little.”

“It isn't the money. Nor is my hesitancy based on the fact that I am unwilling to serve this new country of mine."

His eyebrows lifted and his eyes grew sympathetic.

In answer to his unspoken plea, I told him about Denise Pettibone, of my love for her, of the fact that her husband might be alive. The longer I spoke, the more gleeful the good doctor became. He was a romantic at heart, I found myself thinking. He laughed when I was done and waved a hand.

"Bring the girl along. If you can't marry her, pass her off as your sister.”

I smiled and muttered gloomily, “If she'll come.”

“There is only one way to learn the answer to that, my youthful Hector. You must ask her this very night.”

Denise still wore her peach satin gown, I saw as I let myself into my lodging house. She had discarded the thin fichu, so that her shoulders gleamed nakedly above her low-cut gown as she waited in the hallway.

“David—tout va bien? Is everything all right?”

It was our habit to converse a little in French every evening. I had learned the language from my father and was well versed in it, and Denise had been born in France. Since there are certain things which a gentleman may say to a lady in French without sounding boorish, I had enjoyed our lingual exercises.

It had been an opportunity to flirt, to kiss her hands and even her bared shoulder above the edge of a flying gown upon occasion, and pass it off as practice. She had not been averse to my caresses, but had always held me at arm's length when I would have progressed more ardently.

“Everything has gone very well,” I assured her, and spoke of my talk with Doctor Franklin. She listened quietly, head tilted to one side, eyes grave.

When I was done, she nodded thoughtfully. “You must go, David. And I shall come with you. As this wise man has suggested, to play the part of sister.”

“Sister,” I groaned.

Her plucked eyebrows rose. This evening I found her more radiantly pretty than ever, and my eyes must have told her so, for her cheeks heightened with color and the eyes that looked up at me were overly bright.

“You grow lovelier every moment," I whispered, catching her hands and holding them, drawing her closer.

I am not familiar with women. Most of my life has been spent in fencing salons, but at this moment I understood that Denise Pettibone would not repulse me if I kissed her. My arms went around her, my lips to her mouth.

We clung a moment. I savored the soft moistness of her flesh, knew the hardness of her breasts where they mashed against my chest. For one instant my tongue felt the touch of her own, and then her hands were on my chest, pushing me away.

“Non, non, David. We must not.”

"But why? I love you, you must know that. I want to marry you.”

She shook her head. “We cannot. My husband—”

Denise broke free and walked across the room to stand beside a mahogany pole screen. Her hands clung together, her fingers writhing. Suddenly she turned to face me and I was shocked by the misery in her face.

“Do you think I am happy away from you?” she whispered fiercely. “Don't you realize I would like nothing better than to be your wife?”

Nothing could have kept me from her now. I reached her, swung her around and put my arms about her. My kisses roved over her flushed cheeks and her closed eyes. My hands went down her back to her sides, caressed them through the peach satin.

"No, you mustn't,” she cried.

“You were mistaken about your husband. You had to be.”

She leaned against me in such a way that I could not see her face. Brokenly she whispered, “I am a virgin, David.”

She half laughed when I hugged her. “This pleases you, does it? Ah, you men. But it is true. I have never known a man.”

“But—”

She raised her face, smiled tremulously up at me. “I will tell you all about myself. But first, we must eat.”

I had forgotten about food. My blood was in a ferment from the touch of her body against my own. But when she extended her hand to draw me into the dining room behind the little drawing room, I went with her.

She had laid the table for two, and now she took the tinder box and struck a flame, touching it to the candle wicks. In a moment the room was filled with a soft glow.

There were hot sausages and greens and baked potatoes. I would have protested against eating—there were more important things to be done—but she insisted, with a faint smile, and so I agreed.

Afterward there was a tipsy pudding and cups of hot chocolate. We sat there and smiled at each other, until Denise rose from her chair and came around to stand before me. She bent over, and her bodice fell away so that I could see the inner slopes of her white, blue-veined breasts.

“No, no,” she exclaimed in mock irritation. “It is not the breasts you are to see. It is this."

She tugged at a very fine chain, and upward from between those perfumed orbs she brought a thin medallion. Her pink fingertips made it sway slightly as she held it.

There was a unicorn's head and a fleur-delis engraved on its golden surface. “The crest of the house of d'Aumont. My father is a duke. Charles d'Ausomberre, the duc d'Aumont.”

I sat back, stunned, and stared at her. “A duke! But—"

She put her soft palm to my mouth. I kissed it until she drew it away and shook her head at me in make-believe anger.

"You must listen! Without distracting me. When I was seventeen, Christian Rivarol began to woo me. He was a very fine gentleman, a comte. His family and mine are very old. We have ancestors who fought with DuGuesclin against the English in the Hundred Years War.

"My father did not like Christian. He said he did not trust him. His opposition only made me the more determined to marry him. And marry him I did.

“But—but on our wedding night, before he could make love to me, he left me. Later, when I was beside myself with grief, I heard that he had been killed. It was too late to attend his funeral, but I went to visit his grave.”

I exclaimed, “There, you see! They put dead men in graves. Your husband is in his grave, therefore he is dead.”

“They can put empty coffins in graves, as I now believe was done. I went back to my father, but he is a very proud man. He told me to go away. I was no longer his daughter."

Her lower lip trembled. This time I would not be denied. My arms caught her, brought her down into my lap, where she nestled contentedly enough. Her soft flesh pressing mine, her perfume, made my head swim.

“Fortunately,” she went on, “I had the jewels my mother had left me. With these jewels I would leave France. I was not without sympathetic friends at Court. They interceded for me, and soon I was on a ship bound for this new world, with Achard de Bonvouloir, a French agent disguised as an Antwerp merchant.

“In Philadelphia, where I came, I sold my jewels and bought property. I had scarcely bought this house when you came along, seeking a long room for a fencing salon, and a bedroom.”

I kissed her gently, but before long our tongues were touching, sliding about, and my hands were on her breasts. Her thighs stirred, rubbing together, and I could smell the faint musky odor of her excitement.

She tried to fight me, but very reluctantly, begging me to listen further. “Bonvouloir was here to make arrangements about helping your colonies—please, David! You—must not!”

But I had loosed the strings of her gown. My head bent so that my lips could rove upon the swelling flesh of both her breasts, more than half bared by the down-pulled bodice. The fragrance of her flesh put a fever in my blood.

With both hands she caught my head and held it away from her. Her dark eyes were misted, brilliant with desire. She was as aroused as I, but she fought for control

“You must—listen. You not tempt me—any further. It is—important that I—say what must be said.”

And so I gave in, though I held her against 'me so tightly she could feel the heat of my arousal. She was not displeased with this evidence of her desirability. She was too much a real woman for that, but she was firm in her resolve to go on speaking.

“That is better! You are a very naughty man, mon cher David. Still! I would not have you any other way. Now, then! I have shown you my medallion, among other things. You have seen the crest of my house.

“What you may not know is that my father is very much in favor of helping the Americans to gain their independence from Britain. He lost a brother and an uncle in the last war with England, not quite twenty years ago. I believe you call that war the Indian war, over here."

I nodded. My father had fought in that war, under Montcalm. I said, “Go on. Your father hates the English.”

“And the English know this. I would not be surprised if they struck at him, to dissuade him from continuing this help.”

I began to understand.

“You would like to go home, to see your father again. To discover if he is alive and well. With me."

She nodded, pouting a little. “Is it too much to ask?”

“I'd be the happiest man in the world if you'd marry me, Denise.”

“I cannot marry you,” she whispered. “I must travel with you as Doctor Franklin suggested. As your sister.”

“Sister!"

I moved so that she had indisputable proof of how much I wanted her. She flushed faintly, hid her face again. But she did not stop my hands that caressed her thighs and hips, and, greatly daring, slid under the skirt of her peach satin gown.

Along her stockinged leg and thigh my hand went, slowly stroking. Denise lay with her head back on my arm, her eyes closed, quivering from time to time as her emotions shook her body. Her mouth was open slightly, to aid her shallow breathing.

“David,” she breathed.

“What is it?”

“Would you carry on so—with your sister?”

My hand came out from beneath her skirt as I scowled. My lips opened to protest the fact that her husband might be alive, so there was no need to carry on this pretense. Before I could speak she was off my lap, putting her gown to rights, cheeks flushed, smiling roguishly.

“There. It is better, no? We must be sensible about this. I mean it when I say there must be no more such caresses between us. It is too—exciting.”

She laughed and twisted sideways when I would have reached for her again, slapping my hands. This woman was my entire world, I suddenly realized. Nothing existed for me except her lovely face, her softly curving body. I

“I can't do it," I told her. “How can you expect me to travel with you, day and night—and not reach out to grab you and kiss you? Maybe it would be best if I went to France alone.”

“No! I am to come with you. Once more I must see my father, speak with him. Perhaps—perhaps he has forgiven my foolishness by this time.”

“And if he has?”

“We will enlist his help to find my husband.”

I brightened suddenly. Find the husband, face him with bared steel, slay him. It seemed so simple. It did not occur to my fevered imagination that, if her husband were here in Philadelphia as Denise claimed, he could not be in France.

Nor did it occur to me that Denise might have lied about seeing him earlier this evening.

Please let us know if you like this story in the comments. If there is enough interest, we will publish more of this story.