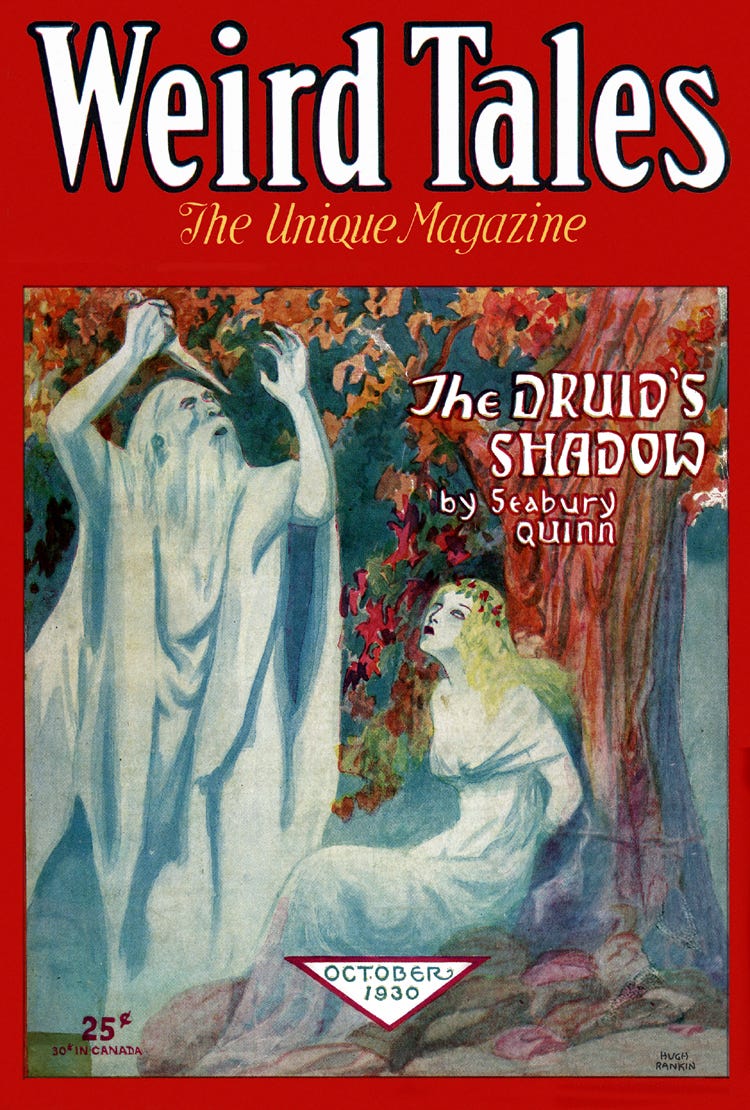

Weird Tales, October 193o

"SPEAKING of jelly-fish," said the man.

We hadn't been speaking of jelly-fish, nor of anything else for that matter, but the tide had gone out and left the rocky strand full of them.

That morning I had left the village soon after daybreak for a ramble along the shore. I had walked a mile, perhaps, beyond the lighthouse and seated myself on a mussel-encrusted rock. The scene was indescribably bleak and lonely. Behind me dark spruce forest presented an unbroken front; on either hand the inhospitable beach stretched away; while in front the long rollers of the Atlantic came in and broke in smothers of foam. Far out, even on as calm a morning as this, I could see the water boiling and seething over the shoals and the cruel ledges of rock which made the approach to the harbor entrance so dangerous a place for ships in stormy weather.

It was while I sat there, thinking rather sadly, and perhaps morbidly, of the many marine disasters the spot had witnessed, that I became conscious of the man seated on another rock not a dozen feet to one side of me. I had not noticed his approach. He was a big man, not so tall as broad and burly, clad in an enormous pea-jacket (I think that is what they are called) much the worse for wear, and with gaping sea-boots on his feet. His hair and full bushy beard, brown in color but shot through with gray, were long and unkempt. A man of about fifty, I thought. At some recent time he had been wet. The water dripped from his clothes. Kelp and bits of seaweed clung to them. Perhaps in clambering over the slimy rocks he had slipped and fallen into one of the many pools left by the outgoing tide. I wondered how he had managed to approach me unheard. But he might have been on the spot before myself, hidden from view behind one of the many huge rocks. A fisherman, maybe; though what a fisherman could be doing in this place, at such an hour, without a house in sight or a fishing-boat to be seen along the shore, puzzled me. However, I wasn't curious—not at first. I drew in deep lungfuls of the damp salt air. Immersed in my own thoughts, I poked with the toe of one heavy boot at a viscous mass of jelly. A queer thing, a jelly-fish. Some of them look like glass, clear as crystal, while others are quite highly colored. But there is an immense variety of them, and often, when the wind blows landward, they are driven onto the beach in thousands. Earlier that morning the wind had blown quite a stiff breeze, though by no means a gale. I recalled once reading that jelly-fish were mostly composed of water-about four hundred parts of water to one of solid matter. There is nothing much to them except water, and yet they live and move, have eyes and ears and locomotive powers, and are able to sting, digest, and reproduce their kind. It was a marvelous thing to think of: living, animate water, swimming in and distinct from water. And yet why be amazed at a jelly-fish? Surely men and animals were just as marvelous. In my own body I was seventy to ninety per cent water. The man on the rock to one side of me. . . . It was then he turned and spoke, the sunlight glinting on his red beak of a nose and hard agate eyes. It gave me quite a start.

"Speaking of jelly-fish," he said, as if reading my thoughts, "I've seen hundreds of 'em, thousands. Not just little fellows like those ones there, but giants" —he made a gesture with his hands— "yes, giants, six, aye, ten feet in circumference, and more than that tall. You've no idea," he said, "what there is down there in the depths of the sea that never comes to the surface, and that no wind blows ashore. But I've seen 'em," he roared, his voice like a fog-horn, like a voice accustomed to shouting against a gale, against the pounding of surf. "Yes, I've seen 'em—me, and two others! Mate of the old Harlow I was. You've heard of the Harlow, as fast and neat a clipper as ever plied 'tween here and London. Three-master, she was, bark-rigged, built at Glasgow in '45, twenty years old, and able to make the crossing in fourteen days. We were the crack ship of the line, old Captain Hayter in command, and Billy Doan second mate. Billy and me had our fortunes told by a slant-eyed heathen in a Limehouse dive who showed us queer things in a crystal ball; aye, bloody queer things. But we were two-thirds drunk. 'Don't go down to the sea this voyage,' he warns. But by the time the Harlow cleared the Thames with seventy passengers and a full cargo under the hatches all memory of the warning had faded. And if it hadn't we would have sailed just the same. For that is the life of a sailor, my lad. Blow high, blow low, he goes down to the sea in ships."

He told me all this in one breath, as it were, and I studied him curiously. His face struck me as being familiar. Somewhere before I had seen it but just where I could not say. The village perhaps. and the name Harlow evoked something that stirred sluggishly in the depths of my mind.

"Blow high, blow low!" he roared. "And she blew high! Aye, she blew great guns. Snow and sleet. And through the snow and sleet, and the blackness of night, under bare poles, we raced before the gale, raced for the harbor entrance, missed it and struck—struck on them rocks out yonder and went to pieces!

"All night," he said, "the bodies came ashore. The coastguards built huge fires and tried to thaw 'em out, but it weren't no use. Corps they were, and stiff and battered. Yes," he cried, "the bodies of the passengers came ashore that night, and the next day, and the next, men, women and children, seventy of 'em, a piteous sight. And the cabin-boys came ashore, and the stewards, and all of the crew—all save the three of us, Captain Hayter, Billy Doan, and me. We didn't come ashore, no. We went down into the sea with the pilot-house around us, and over us, as good officers should, a midsection of hull pulling us down. Aye, we went down; and there we were, suddenly, at the bottom of the ocean, ten fathoms under, and the roar and the noise of the storm was gone, and we were in blackness and afraid. And Billy Doan he gripped me by the arm and whimpered—whimpered like a child, he did—for around our darkness floated strange phosphorescent lights.

"God!' whimpered Billy Doan; and he said: 'D'you remember the crystal? This is what we saw in the crystal.' And the 'old man' was the first to understand, being learned-like and always reading in books. 'Lads,' he says, 'the pilot-house is built of teakwood and the windows snug. It's the air as keeps out the water.'

"Look!' cried Billy Doan in a voice that made me freeze to the marrow. 'Look! what's that?'

"Far away, through ghostly waverings of light, we could see giant jelly-fish advancing. Monstrous things they were, six, aye, ten feet around, and tall—I'm telling you, mate, they were tall, with big saucer-like eyes. Yes, they had eyes! They glued 'em to the glass and looked at us. God! it made the flesh creep the way they looked at us.

For there was no mistaking their looking. Take their turns they would, just like people at a zoo. It fair made the blood run cold.

Billy Doan whimpered again.

"I don't mind being a corp. I don't mind being drowned and going to Davy Jones' Locker proper-like. But this . . . this . . ."

"Then we could see that the ghastly horrors were trying to reach in at us. Long streamers fumbled at the glass windows, beat on them. We could hear the glass rattle. We crouched on the floor, cold and miserable; sick, aye, sick with fear. The 'old man' pointed to a part of the floor some feet away. Ghostly phosphorescent light grew there, a malignant eye, for the flooring had started, and there was a hole in the floor, and only the air was holding out the water. Through this hole, breaking the surface of black water, came a long reaching streamer. It stole toward us. We screamed. Billy Doan screamed. For the streamer had him. It wrapped around his body. Billy Doan fought like a madman.

"O God!' he shrieked, 'don't let it have me, don't!'

"I sought to tear away the slimy tentacle. The 'old man' grabbed one of his legs, but the boot came away in his hands. Down through the hole went Billy Doan, and the giant jelly-fish enfolded him, ingested him, and he was gone. Aye, the jelly-fish had done for poor Billy Doan, and only we two were left, the 'old man' and me. We glared at one another in horror. We backed into the furthest corner of our refuge. Aye, mate, it was ghastly. Two of us alone on the bottom of the sea, waiting, waiting. The 'old 'man' went next. . . . I frothed at the mouth, I tore at my hair in despair, for the phosphorescent light grew, the goggle-eye approached, and the streamer, streamer . . .”

But I waited to hear no more. For an increasing unease brought me to my feet. The wild stretch of shore, the dark forest behind me, the weird story of the madman (for I was positive he must be daft), all these things together wrought havoc with my nerves. I walked swiftly away, and after a few yards I looked back and he was standing up and waving his arms at me. I turned away. When I glanced back again he had disappeared. As I say, there were plenty of large rocks, large enough to conceal a man. Nevertheless, I started to run, and I never stopped running until I reached the village. Outside the village I met a coastguardsman. He shook his head.

"No, sir, I don't know of any such man."

I still persisted. He gave me a peculiar look, I thought.

"There ain't no crazy man in these parts, sir."

I made discreet inquiries in the village, but to no use. Fed up with my holiday I took the government boat that afternoon for the city. I had no longer any desire to tramp bleak seashores. And that is the end of the matter, save for one last thing.

Three months later I was paying a visit to an aunt of mine in Boston. Hanging on the parlor wall was the painted picture of a man, a man with bushy brown hair and beard shot through with gray, a red beak of a nose and hard agate eyes a man perhaps fifty years of age. I stared, thunderstruck, for the painted likeness was that of the singular individual whose mad tale I had listened to on the beach.

"Who—who is that?" I faltered.

"Why," said my aunt, "that's a picture of your great-uncle Jim, your grandfather's brother. Surely you've heard about him. He was drowned, and his body never recovered, when the old Harlow went down off Sambro."

END