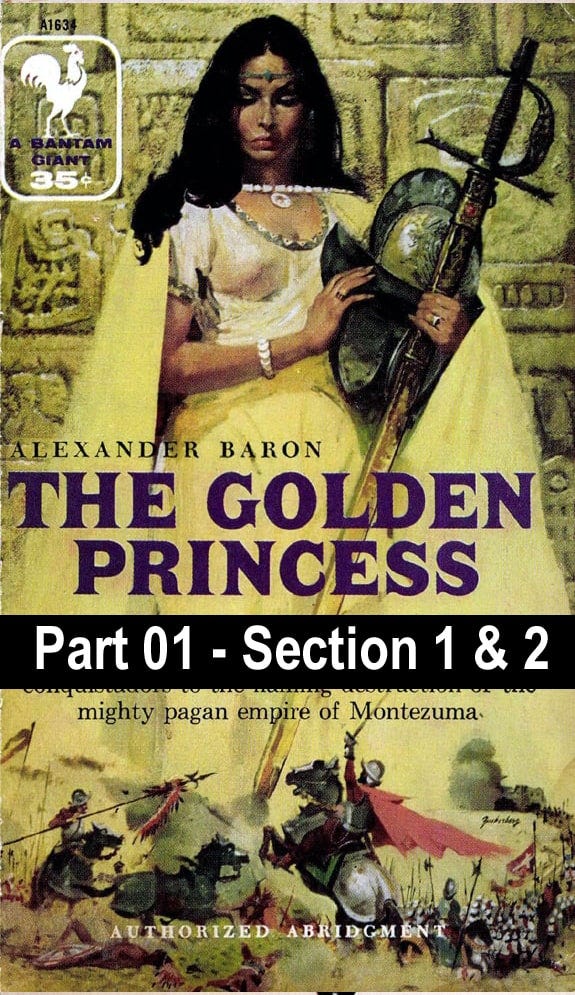

The Golden Princess by Alexander Baron - PART 01 - sections 1 & 2

Genre: Historical Fiction / South America & Conquistadors

The Golden Princess by Alexander Baron was originally printed in 1957.

A novel of the hot-blooded Indian mistress of Cortés who led him and the conquistadors to the flaming destruction of the mighty pagan empire of Montezuma.

THE PRINCESS AND THE CONQUISTADOR

Her name was Marina. Born a princess, she was given to the conquistadors as their slave girl by the Indians for a peace-offering. From her first sight of their leader, Cortés, she adored him. Then he took her for his own and she knew he was a god—her god.

His name was Cortés. Brilliant leader, mighty soldier, man of incredible cruelty and ambition, Don Hernando Cortés craved power as insatiably as he did women. To gain an empire—or die—he landed on the coast of Mexico with only four hundred men—and burned his ships behind him. Using Marina as his eyes and ears he faced the overwhelming Aztec hordes with but one purpose—conquest, bloody and absolute.

PART ONE

MALINALI IS BORN AGAIN

1.

Malinali was not greatly disturbed when she heard that she was to be given to the white strangers as a peace offering. Probably none of the girls were surprised.

There were twenty of them. In the last five days the whole universe, as they and their kinsfolk knew it, had been smashed to fragments, and now that it was taking a new shape, it was like a dream. Nothing in a dream is surprising. Each event that follows, unreal, inevitable, is accepted as a matter of course. The apathy of dream lay heavy on the whole town, on every house, on the temple.

For centuries the little town had lived in peace beneath the vast, empty sky. All creation was flooded with sunlight.

The waves, rhythmic and translucent, had come running in from the blue expanse of the sea, setting up an endless, lulling roar as they broke on the white sand. The men had fished in their canoes; the women had squatted within the white lime-washed walls of the mud-brick huts, ground their maize, brewed liquor, and tended the crops. The plain, intersected by irrigation ditches, was rich. There was enough for all.

Thus it had always been. Thus it would always be.

The course of life changes in a second. An event splits the sky like lightning and the foreseen future, the expected continuation of the past, vanishes in a thunderclap. It was five days ago that they had seen the white wings far away from the sea, near to the skyline. The rumors spread. The wings grew larger. They skimmed the sea, borne on great black bodies. Gliding over the water, they came to the sand bar outside the river. There were six of them. They came to rest. Now, the men with their weapons, the women from their houses, some silent, some murmuring, all watched. Fear and premonition touched the hearts of the people, and they hid among the mangroves as they watched. That was five days ago.

The terrible things that had followed had frightened Malinali, but they had not left her with the same anguished feeling of total disruption that had stricken her neighbors There was a reason for this. She was not one of them. She was a slave. Five years before, something had happened to her that had been as final a calamity as these happenings must now seem to the townsfolk. Since then, if the sky were to fall in, she would not feel greatly concerned. She neither liked nor disliked the people. They treated her as they might treat one of the little hairless puppy dogs that they kept in their houses, fed, petted, and in time, ate. Her religion, and her upbringing as a woman, had both taught her that whatever happened was her lot, to be accepted without rancor. However, she had been revered, and now she was unnoticed. She had once been pampered with luscious dishes, served to her on glittering platters. Now she ate the maize that her master's family left. She could not help feeling, in the midst of her fear, a faint satisfaction at what was now befalling them.

Canoes had put off from the sea monsters. When the men pulled their canoes up onto the beach, they were seen to be much bigger than the men of this country, many of them with metal helmets and shining silvery breastplates. Their skins were light, some little paler than those of the townsfolk, some pink as the paws of newborn puppies. Strangest of all to the smooth-skinned natives, they had thick beards of red and brown and black. And they all seemed to talk to each other in shouts. Who had ever heard of voices being raised as theirs were boisterously raised?

The townsfolk might, from the beginning, have given them what they wanted. But strangers like these had been seen before, only the previous year, and had been allowed to depart in peace. Since then, all the tribes, all the villages of the interior, had taunted the people of the coast. The name of coward lay upon them, and they were eager to get rid of it.

They had agreed, too, that there was no knowing what evils the strangers might bring if they returned. So they resisted.

At first, a few young men in canoes approached the strangers with warning flights of arrows. The strangers cast thunder and lightning at them, and the canoes sank, and there was blood on the water. The strangers landed. When they were all mustered, the count reported by the native scouts was only four hundred. Raiding parties were sent. Thunder and lightning scattered the raiding parties.

Then the priests and the elders met to consider this new threat seriously. Envoys were sent to all the neighboring parts.

Confidence came back as the whole countryside assembled in arms. Here was a sea of warriors that would daunt the gods. The band of strangers had moved out, three hours' march, into the plain, to make a camp. On the fourth day, when all the war parties were assembled, the tide of warriors had rolled down upon the strangers.

Who could have angered the gods? How was it that the arrows and stones of forty thousand warriors had rattled like hail off the bodies of these more-than-men? What were the discharges that mowed down wave after wave of warriors?

What were these strange creatures, half-man, half unknown four-legged beasts, that charged into the midst of the warriors with devastating sword and lance, leaving lanes of dead and wounded behind them?

By nightfall the plain was silent, covered with dead, and all the dead were dark-skinned. The strangers were camped in the courtyard of the temple. The warriors hid in ravines or in their houses, and the women crouched in dark corners, remembering dead husbands and sons. The next day the chiefs went to the strangers and asked for peace. Today they were still in conference.

Townsfolk came, bringing maize to eat, and fruit, and dogs, and trinkets of yellow metal, which—they reported—the strangers seized upon with unaccountable eagerness. It had been suggested, by some wise man among the chiefs, that the most acceptable offering of all was yet to be made.

And now the offering, the twenty girls, waited.

Malinali was unmoved. For one thing, her disaster had already occurred, and another change of fortune mattered little to her. Indeed, she was impressed at the opportunities that a change of master might offer, especially when the new possessor was as powerful as these men were. For another thing, she was curious. Her life for the last five years had been a lonely, secret existence. She had never cultivated more than a superficial friendliness with the girls among whom she lived.

All these years she had known that she possessed something that none of these girls had—an intelligence hungry for fodder, that had been working secretly within her. Now there was a new object for it, new things to look at, new things to learn, new possibilities which excited her.

She was in no doubt about one thing. These strangers were men and no more than men. It was doubtful if anyone in the town, at this moment, shared this belief. But she knew.

And, because she was a slave, and a stranger, and liked to live with her own thoughts, she kept her knowledge to herself, as she had done—when was it?—oh, a full year ago.

She had met one of them, a man with pale skin and a bush of hair upon his face, lying exhausted upon the beach.

She had fed him and comforted him as a woman. A household beast for these last few years, it was as natural for her to proffer her body to a man as it was to bring him food.

He had been frightened. He had refused to come into the town; and because she, too, was a stranger in this place, she had helped him to find a hiding place in the forest and had gone to him every day. The fact stuck in her mind: he had been frightened. That was important to remember when all the people were now frightened of men like him.

Going to him every day, and lying on the dull white sand at his side, she had learned to pronounce his name—she savored it now, Juan, and she had learned many words of his tongue. Certainly, she had learned many words from him.

When they were able to talk, he told her that his boat had sunk, and everyone but him had drowned. Boat?

Many men? She looked at the sea monsters with understanding eyes. And in all his stay in the forest, no one had found him.

The people had kept away from the place, for the word had spread that a pallid ghost had been seen flitting among the trees; and everyone lived in perpetual fear of spirits. It was funny—a great, secret joke to Malinali. Of course, she believed in spirits, like every sane person. But every flitting shadow, every unfamiliar noise in a dark place, need not be a spirit.

At last, Juan had gone away to the south, and she had never seen him since; but he had left his words behind with her, and she had taken great pride in them, never revealing them to anyone, uttering them soundlessly within her mouth, building on them a whole structure of dreams about him, and the wonderful things he had told her, and thinking, thinking, about all the men like him who lived, as he had told her, where the sun rose. Men—yes. At the age of eighteen, she knew all about men. They had been using her for their purposes long enough. And, meeting Juan, she had learned enough about his ways, his weaknesses, his conceits, his body, and his needs, to decide quite firmly that he was no more to be feared than any other male she had had to reckon with.

She marveled as she listened to the talk around her, at the stupidity of her masters. "Sea monsters," indeed! And those who talked were supposed to be priests, chiefs, sages!

All that had to be done, to see through any mystery, was to keep down fear, to look at it calmly, to let that wonderful gift, her secret, her intelligence, examine all its details; and intelligence, that joyful turmoil in the head, quietened down to a voice that told all. The monsters were nothing more than canoes, each as big as twenty canoes. The dazzling white wings were only woven sheets, which the wind filled to drive the canoes across the sea. It was a wonderful idea—but the breeze did it with every leaf that fell from a tree to drift out over the sea. What was magic about that? The four-legged monsters and the deadly lightnings? A spasm of terror stilled her reasoning. She had to take hold of herself and tell herself that, they would protect her, as their property, from the disfavor of their gods.

Keep calm, wait, learn, and be what you were born, a princess!

So she waited, standing among the other girls, quiet and impassive.

There was a great wailing going on among the other girls.

She recognized, with some amusement, that their lack of imagination saved them from the same gripping terror that sickened their families. Even before the event, sex bound them to their new masters. They stood with their mothers and sisters, wept, and exchanged parting embraces, but many of them with no more than the dutiful demonstrativeness that was expected of a girl before her marriage. Some, conscious of the eyes of awed crowds upon them, were positively showing off. Others huddled in flaccid heaps. She walked a few paces to one of these girls, stooped over her, and stroked her hair. The girl raised her head and managed a faint smile of gratitude.

When the town elders led the way to the stranger’s quarters, Malinali, walking sedately, was the first girl to follow.

2.

The event that changed Malinali's life took place on the twenty-sixth day of March, in the year 1519. It was some time before she was educated sufficiently to know this, and by that time she had learned many other things.

Since the discovery of America by Columbus, only twenty-seven years before, a stream of Spanish settlers and adventurers had been crossing the Atlantic. The adventurers, in their two-hundred-ton cockleshells, sailed among the islands, killing, plundering, looking for gold and slaves, lured on by the fascination of monstrous legends—the tales of two-headed giants, kingdoms of Amazon women, above all, of El Dorado, the land of gold and precious stones—in which they believed as literally as they believed in salvation and hell-fire. The settlers rounded up slaves, farmed, traded, and built towns.

Don Diego de Velazquez, the Governor of Cuba, was one of the architects of colonization He had been a good fighter in his time and had led the conquest of Cuba. In the founding of cities and the establishment of an ordered government, he had shown himself a man of some vision. Comfortable in his office, however, and made complacent by the powerful backing he could count on in Spain—he was related by marriage to Juan Rodriguez de Fonseca, the Bishop of Burgos, who controlled the Council of the Indies on behalf of His Imperial Majesty Charles V—he had, in recent years, been content to rest on his triumphs.

Big, handsome, and jovial, he enjoyed life and reveled in the popularity that men of his stamp can command at the center of a community that vied in chivalry, luxury, and dissipation with the Castilian court itself; and he was growing fat very much rapidly. Now he could order other men to do the adventuring.

He had sent several expeditions sailing off into the blank western seas, in search of the wondrous lands that must surely lie beyond. Some had met with disaster; some had returned and reported that there was land to the west, a sandy coast with Indian inhabitants, but no more.

He decided to send another expedition, and at great expense began the fitting out of six ships. Recruiting, taking in stores, planning—these were weary and complicated jobs, and he was grateful when a young protege took them over for him. The young man, whose name was Hernan Cortes, went about his task with a furious efficiency that impressed Velazquez.

He knew that Cortes was hot with ambition to win wealth and glory for himself. He had watched over Cortes for fourteen years, ever since the young man, at the age of twenty, had arrived from Spain. Cortes had fought under him in the conquest of Cuba and had shown himself to be brave and resourceful; had been his secretary, relieving his master of all the weary business of drafting pronouncements, settling lawsuits, and handling correspondence, showing himself tireless, subtle, and cunning; had done well as the mayor of the town of Santiago; and had mined gold and farmed cattle with great success. Cortes had won a reputation for boldness and daring, and if much of it was earned in amorous escapades and brawls with sword and dagger, that was no less a commendation to Diego de Velazquez.

Cortes traveled about the island recruiting soldiers and sailors with promises of gold and renown—primarily of gold.

He sold his mines and his slaves, mortgaged his lands, borrowed money from merchants, persuaded his friends to contribute loans, put in every penny of the fortune he had saved, and invested as much in the venture as Velazquez. The Governor appointed him captain-general of the expedition—then had second thoughts. If chivalry was the face of life in this second Spain, treachery was its mainspring. Every man had come here for his own gain and glorification, and every comrade was a possible rival. Cortes had been his choice as a man who had always served him well, and who was most likely to bring credit to Velazquez. But Cortes, with this new responsibility, was like a man who has always stooped and now shows his full stature for the first time. He blazed with energy; he spoke fearlessly, even curtly, with Velazquez, as if the Governor were no more than some tiresome port official.

Rivals, and the friends of rivals, were not lacking to warn Velazquez that he had picked a man who might be too big for him.

He gave specific orders to Cortes defining the aims of the expedition. These were to survey the coast and to barter with the natives. No more. If Cortes were to do this and then report back, Velazquez could take control himself.

But he was still worried, and one night he decided to remove Cortes from the command. He told only two trusted advisers and went to bed. It would be time enough to tell Cortes in the morning. When he awoke in the morning, Cortes and the fleet had sailed.

The women stood in a silent group. Most of them, including Malinali, had nothing better to wear than a shabby old blanket; evidently fear had not stampeded the townsfolk into being overgenerous.

The deputation of chiefs had paid its respects to the strangers, and gifts were being laid at the white men's feet.

Under her blanket, Malinali felt her body quiver like an animal's. Her insides were chilled. It was fear, the fear that kept coming back upon her in spite of her attempts at self-command

To be cast afresh into the unknown was frightening.

She forced herself to look about her, to find calm by absorbing herself in her surroundings. There were treble ranks of white men to the right and left. It was their voices that made everything seem strange; loud and echoing in the sunlight, violent as blows, so different from the soft native voices.

And their clothing, molded to their bodies, so tight, and of so many colors, instead of the loin-cloths of the local men.

Everything about these new men was abrupt and violent.

Their weapons flashed in the sunlight, swords, silvery lances, and cumbersome strange implements she did not know. Most of the other women could feel themselves being eyed by the men, and in spite of their fear, they began to look back with a brazen female curiosity.

In front of her were the chiefs of the white men. Now she began to look at them one by one. The leader was sitting back thoughtfully in a chair, his cheek resting against the fingers of his right hand. He was talking quietly to a man on his right—the quietness of his voice struck her, after hearing these other men. The man on his right rose and began to speak in her own tongue. The interpreter was Juan, the man she had known a year before. She had vaguely assumed that, if other men of his kind had come to these shores, he would rejoin them. After the first quick heartbeat of recognition, she did not feel excited or glad. She remembered him with no special affection; he had just been a man encountered, like so many others. He did not seem to be important among the other white men, but all the same, it was reassuring to feel that there was one known person among these men.

Juan was saying, "We are glad to hear that you wish to live in peace with us. We are glad that you will allow us to pass freely through your lands, and will give us all the food we need. But my commander has told me to tell you that he has taken possession of this place in the name of our great king beyond the seas. We shall go away, but if there is any sign of rebellion we shall come back, and put every man, woman, and child in it to the sword."

She was not very interested in the speeches. The face of the white chief fascinated her. It was thin, thoughtful, brooding.

The man appeared quite young, well made but slender almost to leanness. He was dressed quietly in a costume of gleaming, metallic gray. He wore a thin chain of gold around his neck, and Malinali, as the nearest of the girls, could see that from it hung a little image of a woman with a baby in her arms. He kept his chin cradled in his fingers. He did not look once at the women and gazed intently at the native chiefs.

She took notice of some of the other men around him. There was a standard-bearer behind him, and a little boy to whom she at once applied the word "beautiful" and who could not have been more than twelve years old. The boy was dressed in exactly the same colors as the chief. Seated on the left-hand side of the chief was a young man, with a fine handsome face whose skin was almost as smooth and brown as her own. The young man had the bearing of a chief, and his clothes—black and plain and fitting like a sheath touched here and there with small gold ornaments—appeared of fine quality; but, unlike the other leaders, he had no beard. He consulted from time to time with the leader and was writing or drawing something in a book. Among the warriors who stood behind, fine, big, bearded men dressed in gay colors, she noticed one in particular: a man who stood head and shoulders above even his comrades and who had hair as blazing gold as sunlight. There were two men standing off to one side of the group who both wore a different garb, robes with plain girdles at the waist and tunics beneath; one in black, the other in white. Their heads were shaven, each with a ring of hair left, and they stood listening with bowed heads. Her gaze returned to the leader, and thereafter she had eyes for no one but him, studying every glance and movement that he made.

The ground in front of him was covered with gifts, succulent little pigs with their legs hobbled, chickens, heaps of maize cobs and cacao beans, beautifully colored blankets, and feather mantles, and yellow metal trinkets. He leaned forward and picked up a collar that consisted of three coils with the head and tail of a serpent. He spoke to Juan, the interpreter, who said to the native chiefs, "Where does this metal come from?"

Again the strange interest of the white men in this metal. Oro was the word she heard Juan use for it. She memorized it carefully. Perhaps it had some religious use, or perhaps some worth as cash, for she knew that the merchants from over the mountains carried quills full of its dust as a medium of exchange.

Tlahuicol, the white-haired elder, pointed to the west.

"From there."

The strangers turned and looked. The plains stretched far.

Beyond rose a jagged rim of blue shadows, the great mountains.

"Beyond the mountains."

"How far beyond the mountains?"

"Very far."

The leader of the conquerors leaned forward. Malinali saw that his face was intent—fanatically intent. "How many days' march?"

As soon as he spoke these words in his own language, a strange thing happened. The men behind his chair uttered exclamations to each other, and there was a stirring among the soldiers nearby. Malinali had the feeling that these sounds and movements somehow expressed protest or consternation.

The white leader half turned in his chair and uttered a curt command. His men fell silent again.

"None of our men has ever been there," Tlahuicol answered.

"For the messengers of the great emperor, it is many days' march."

"Who is the great emperor?"

"The emperor of all the peoples in this land. The chief over all the chiefs."

"Have none of you ever seen him?"

"None of us."

"Where does he dwell?"

Tlahuicol pointed again to the west. "In the City of Mexico."

The white chief sat upright and looked to the west, and he said in a quiet voice, "Mexico."

Then he rose and saluted the native chiefs courteously with his right hand and told them that they might go.

The girls waited to learn how they were to be disposed of.

Some of the common soldiers crowded about them, but a guard marched up and kept the girls apart. Juan came and told the girls to follow him. As he spoke he saw Malinali. His gaze rested on her for a moment. He turned away, looked back with a slight, puzzled frown, then turned again to lead the girls away. Malinali made no attempt to speak to him.

Silent and patient as a cat, she followed. At the door of a large hut, he spoke to the girls. "You will stay here. There is food and water inside for you. There will be a guard to keep the men away from you." All the time his eyes were on Malinali.

The girls went into the hut, in a flow of chatter. As Malinali came past him, she said, "Juan?"

He uttered a short laugh as if derisive of his own forgetfulness.

"Ha! Of course!" He turned away. He saw her lingering, and said, "Well? Inside with you!"

Although she gave no sign of it, she was taken aback.

"You did not remember me?"

"After all that time? There have been a lot of women since you, little one, and they all look very much the same to me." He spoke in her language, which he had mastered well.

Softly, with a secret, joyful pleasure at using the words aloud, at last, she said, in his tongue, "Me, you, Juan, Malinali, Malinali with Juan, yes?"

Another bark of a laugh. "By Our Lady, you are as clever as the parrot birds they have in this country." He turned away again.

Now she was smitten with a deep feeling of rebuff. Rapidly, in her own tongue, she said, "Shall I be your woman, Juan?"

He turned on her. "What do I want with a woman?" His face was congested with anger. "Did you not see me limp as I walked? Look at these sores around my mouth! The cursed disease is eating me that a man gets from women, and you ask me if I want you!" He made a sound of disgust.

She said humbly, "It was not from me, Juan."

"No, but it was from one of you, somewhere. Do you think I've a taste for any of you now?"

The girls had settled themselves and were crowding back to the door. One of them asked shrilly, "Where is my new master? I would rather stay with him than with a lot of cackling hens."

"You cackle too much yourself," Juan said. "Your men will have you when you have been cleansed."

"I told you," Malinali said, with some annoyance. "I am clean."

"Of yours sins, woman," he answered impatiently. "The priests, the holy water."

Juan left them and the girls drifted back to their sleeping mats. Malinali claimed her corner, helped the scared girl to find a place, and exchanged a few friendly words with the others, for although she was reserved she was not unsociable.

Then she sat by the door and gazed out past the guard. Fear was creeping in on her like dusk. The leap of confidence she had felt at the sight of Juan was gone. She felt lost now, alone, like a child; as much as any of these girls, although she did not show it. And what had he said? "The priests? The holy water?" A cleansing? What cleansing? Fear and mystery were upon her when she lay down that night.

The moment of awakening the next day was itself a blow to her courage. She was still trying to rally herself when Juan came in. He ordered the girls to bathe and left clean white garments for them to wear. All the girls were looking at each other, dumb-struck, wide-eyed, wondering if they were to be sacrificed. But when the cleansing came, Malinali laughed and said to herself, "You see, you must not be frightened by new things!"

The girls stood in a courtyard. The soldiers were there, too, in rows, all very quiet. In front, there was some sort of altar and the elder of the two robed men Malinali had seen yesterday, the one in white. Evidently, he was a priest. There was an image behind the altar that puzzled her. It was of a gaunt, bearded man nailed to a cross. And nearby there was another image. It was of a woman with a baby in her arms. Hadn't she seen?—yes, of course, the white men's chief, yesterday, had worn the same image in miniature on his breast. Perhaps it was his mother? Perhaps the white chief was also a priest and the child of a god? But—this gentlewoman, this tortured man. Were they gods? Surely not. How could one quail before these?

The priest was speaking. He was a middle-aged man, with a leathery brown face and a ring of gray hair. His eyes were keen and good-humored There was a sternness in his manner, but also friendship and Malinali felt reassured. Juan interpreted.

There was something about a One God, who could not be seen ( then who were these images? It was all very strange) but who was everywhere. (Where? She looked up at the sky. Then she looked at the man on the cross. Was this a god? She did not want to cringe before him; she wanted to mother him in his pain. And the woman, she could go to one like her as a daughter. Her own mother—pain stabbed at her, and her attention returned to Juan's words.) The old gods were not really gods but evil spirits. (Naturally, he would say that. But—what about the white men's thunders and lightnings? It was better to believe what he said. She looked again at the gods behind the altar. Who were they? Could these really have beaten the huge, square-faced, cruel-faced gods she knew?) This life was only a brief moment compared with another life that followed. ( She paid fervent attention here. Her lips were parted, her eyes fixed upon the priest's face.) The other life went on forever and ever. Those who worshiped the old gods spent that life in a huge fire, never able to escape. The flames licked at them. Their flesh roasted. Their blood sizzled. They shrieked with pain. They writhed. They clawed the air. And they went on suffering forever. (Her heart beat fast. Amazement, terror, and incredulity chased each other in a circle inside her.) But those who worshiped this new One God had a wonderful, happy life forever and ever.

And the white men had come here to tell everybody about this new God, and to give everyone a chance to choose between the fire and the happy place.

She gazed around her. She could only clutch vaguely at what she heard. The priest was pointing at the image of the mother and child. This was his mother, Mary, and even when she held her baby in her arms, she was still a virgin. That was the first magic the god did on earth. He wept about, and he taught men, and he did a lot of magic, but bad men, who did not believe him, nailed him to a cross ( ah, now she understood!), and he died. He let himself die, to be a sacrifice, for the good of all men. After that, all other sacrifices were absolutely forbidden. (They didn't like human sacrifice, then, these white men? Nor—the thought had been smothered for years at the bottom of her mind—did she. In her native country, down in the south, it had not been allowed. Everybody had been kind and gentle. She looked up at the image of the Mother. A mother! Oh, to have a mother, a mother who would not„ Once again she stamped on her thoughts.) She looked, now, at the new religion with eyes softened by her mood.

The girls went forward, one by one, scared and dazed, and the priest touched each of them with water to wash away their past lives, and he spoke over them and made a sign, and he gave each of them a new name for her new life.

Malinali heard her new name spoken, and she looked up at the priest and repeated it, "Marina."

She went away hugging her new name as a child hugs a doll. She would live forever and ever. Oh, how beautiful!

She loved to live, even when times were hard for her. Merely to open her eyes and feel the daylight upon them, to feel the air upon her cheek, the cool sluicing of water upon her skin, to see scarlet flowers and glossy green leaves, was a glorious privilege. And this was going to last forever and ever and ever because in this new religion death was just a door to another life, an always-happy life. And the new name was part of her new status, this new beginning. Even if she had to slave in the future, she did not feel like a slave at the moment.

No more Malinali! Marina, Marina, Marina!