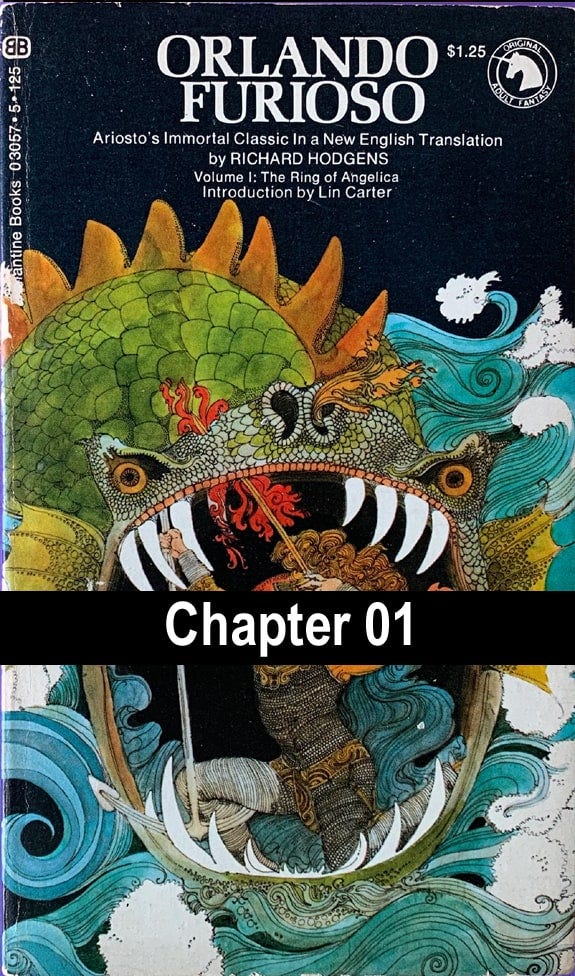

Orlando Furioso translated by Richard Hodgens - Chapter 01

1973 Genre: VIntage Paperback / Sword and Sorcery

A NEW PROSE TRANSLATION OF---

Ariosto's epic fantasy of the age of chivalry, thronged with sorcerers and hippogriffs, ladies and their—knights, magic rings, wondrous swords, magnificent horses, and more plots than you can shake a sword at. An ebullient dreamworld, teeming with life, laughter, and a super-colossal cast of world-renowned heroes.

ONE

Fountain of Disdain

I celebrate the ladies, knights, arms, affairs, ancient chivalries and brave deeds of that time when the Moors of Africa crossed the sea and ravaged France, following the wrath and youthful fury of Agramante, their king, who boasted that he would avenge the death of his father, Troiano, on Charlemagne the Roman Emperor.

I shall tell also those truths about Orlando never before put into prose or verse; how love drove him to fury and madness, exceeding wise though he was before he loved. . . . At least, I shall tell you all I promise if the woman who drives me almost as mad with love-troubling my mind, hour after hour—will allow me enough strength and time to finish.

Ippolito, generous son of Ercole, ornament and glory of our age, accept this work penned humbly in your service. I can repay what I owe you only in part with this writing. It is not much; but what little I can give, I do give to you. And among the worthiest heroes I intend to write about you will find Ruggiero, your own ancestor, the founder of the House of Este. You will hear about his great bravery and brilliance, if you listen, if you can put aside your own cares and concerns for a while, or can find time among them for my tales.

Orlando, who for so long had loved the beautiful Angelica, Princess of Cathay, and who had won innumerable immortal trophies for her—in India, in Media and in Tartary—had now returned with her all the way back to the West, where he found Charlemagne encamped with the forces of France and Germany on a field below the great peaks of the Pyrenees. The Emperor and his host were waiting there, ready to make Agramante and his ally, Marsilio of Spain, bitterly regret their folly in having led their great armies across the sea and over the mountains to destroy the beautiful realm of France. Orlando arrived (at long last) precisely at the time when battle was about to be joined—and soon regretted it.

For then and there his lady was taken away from him. How often human judgment errs! He had defended her from far eastern to far western shores, and now, in the midst of his friends, in his own land, she was taken away, without even the drawing of a single sword. Wisely, his uncle, the Emperor Charlemagne, wanted to evade a contest over Angelica between Orlando and Rinaldo on that day of battle. Once before Angelica had come to France, escorted on that occasion by her brother Argalia. He had lost his life, but she had distracted all the Emperor's knights with her beauty. He was not happy to see her again, welcoming only Orlando, gone for so long on account of her—and now threatening a fight with Rinaldo on account of her.

Charlemagne did not care for such quarrels, especially not at such a time. He took the lady and put her in the keeping of the old Duke of Bavaria. Cannily he then promised her as a prize to the knight who killed the largest number of infidel invaders in the great battle ( thus proving once again his enormous capacity for statesmanship).

But it proved impossible for him that day to count the dead or award any prize. His forces were scattered.

Along with many others, the Duke of Bavaria was taken prisoner and his pavilion was abandoned in the rout.

There the lady had awaited the outcome, until it seemed clear to her that Fortune was turning against the Christians. Whereupon she mounted a palfrey, watched a while longer, and fled when she had to—into the deep forest by the field. On the narrow path she met a knight coming the other way on foot—all his armor on, helmet on his head, sword at his side and shield on his arm, but running through the wood more lightly than a half-naked athlete racing in an open field for a prize. Angelica wheeled her palfrey round in the narrow way as quickly as though she had stepped on a snake—for the knight was Orlando's cousin Rinaldo, Lord of Montalbano, son of Duke Aimone of Clermont.

Rinaldo, having lost his horse Baiardo in the battle not long before, was looking for the beast. But as Angelica turned to flee, he recognized her—the lady who had once loved him, and whom he now loved so much. He forgot his horse: He forgot his battle. Running even faster, he hurried after his lady.

She turned the palfrey and drove into the depths of the wood, not down the path back to the battlefield.

And in the wood she drove not down the safest way, but recklessly, anywhere. Pale, trembling, crazed with fear of Rinaldo, she let the palfrey choose the way in the wilderness, only urging him on with her heels. And he raced on until he came to the bank of a river.

There the pagan Spanish knight Ferrau stood, covered with sweat and dust. He had left the battle a while before and had come to the river to drink and rest. He was still there because in his eagerness to drink he had carelessly let his helmet fall into the stream,' and he had not been able to retrieve it. As Angelica burst out of the forest, calling for help, Ferrau jumped up, saw her, and knew her well, though it was many days since he had heard of her, and many more since he had seen her. He was the knight who, hoping to take her when she first came to France, had killed her brother. Further, he had taken her dead brother's helmet and had kept it—until he lost it that day in the river.

And because he was courteous and brave and still wanted her anyway, he answered her call for help as readily as if he still wore her dead brother's helmet, or any helmet at all; drawing his sword, he challenged Rinaldo, who followed close behind her. Rinaldo was not afraid of him. These knights not only knew each other by sight, but had crossed swords before. And just as they were—both on foot and one without a helmet—they began to fight with their naked swords, hammering fiercely at each other's plate and mail. Metal soon buckled and broke; anvils could not have withstood the impact of their swords. And while they fought, Angelica drove her palfrey on through woods and clearings as fast as she could.

After the knights had fought a while in vain, neither wounding nor moving one another, only damaging armor, their skill outwitting their strength, Rinaldo, his voice choked with anger and desire, said to the pagan, "You're harming yourself as well as me by. keeping me from her. If this goes on—even if you win—what will it matter? She won't be yours, either; she will be gone.

It would be better, if you want her too, to catch her before we settle this and before she goes any farther!

When we have her, then we may decide who gets her.

Otherwise, I don't know how either one of us will get anything out of this."

The proposal did not displease the pagan. The combat was postponed. In their truce, the knights forgot their anger and hatred so completely that when Ferrau left the riverside on his horse, he did not leave the good Rinaldo behind on foot, but invited him to mount up behind him on the croup—and only then did the two amicably gallop off on Angelica's trail.

The knights of old were very good that way. These two were rivals, they were of different faiths, it was wartime and they still ached all over from the impact of each other's swords on their armor, yet they rode together down a crooked path in the deep woods in perfect trust. Driven by their four spurs, however, the horse soon came to a place where the path divided in two. They did not know which branch to take, since both bore fresh tracks. So they left it to chance. Rinaldo dismounted and walked one way, and Ferrau took the other.

Ferrau was soon bewildered. Circling about, he found himself at the river again—at the same spot where he had dropped his helmet in the water. Having no longer any hope of getting the girl, he went down the bank to the edge where he had knelt to drink and so lost the helmet. He had realized at the time that it was caught in the sandy bottom and knew it would not be easy to recover. Now he took a great branch from a tree and made a long pole to probe the bottom. He searched, but he could neither see it nor feel it with the pole. Still, he was too irritated and stubborn to give up. He persisted until he saw the head and shoulders of a fierce-looking knight emerge from the deeper water in the middle of the stream.

This knight was fully armed, except for his dripping head. But in his raised right hand he held high a helmet—the very helmet that Ferrau had wasted that long afternoon trying to dredge up.

Opening his mouth, waiting only for the water to spew from it, the knight sputtered angrily, "Ah, breaker of your faith and your word! Swine! Why worry about leaving the helmet, too? This helmet, which you ought to have returned to me a long time ago! Remember how you killed Argalia, Angelica's brother? Remember the man you killed? I am he! I am Argalia!

"And remember how you promised to throw my helmet in the river—after my corpse and all my other arms. Now that Fortune has forced you to keep your word at last, do not be so disturbed about it. If you worry yourself about the helmet, worry rather that you broke your word.

"If you want a fine helmet to wear, find another.

And wear it with more honor—one like Orlando's, or Rinaldo's. Orlando's helmet was Almonte's; Rinaldo's was Mambrino's. And those Christian knights killed pagan enemies and won the helmets fairly. Get one of them—as fairly. This one, which you gave your word to leave to me, you had better leave to me, after all."

At the sudden apparition of Argalia in the river, the Saracen's hair stood on end, his face lost color and his voice died in his throat. Then, hearing Argalia rebuke him for breaking faith, he burned with shame and anger. Not having time to think of an excuse, and knowing very well that what the apparition said was true, be did not even try to speak before it disappeared—slowly sinking back into the river. But in his overwhelming shame, Ferrau now swore by the life of his mother Lanfusa never to wear another helmet—except the one that once in Aspramonte, in Calabria, the young Orlando took from the head of the fierce African, Almonte, the brother of that King Troiano whom Orlando also killed when the Africans last invaded Europe. This new vow Ferrau kept better than he had kept the other one to Argalia. He moved away, ever onward, ridden without cease by shame and sorrow, intent only on finding Orlando in order to take the helmet.

A different adventure befell the good Rinaldo, who had walked down the other path; he had not walked far before he saw his destrier Baiardo leaping ahead like a horse wild in the woods again, as when he had first found him, years before.

"Stay, Baiardo! Stop!" he yelled. "I need you!"

But the horse did not listen and did not come to him; instead, it went on even faster.

Rinaldo hurried after, burning now with anger as well as with love.

But we follow Angelica, who had also fled. She fled through dark and frightful forest, uninhabited and wild.

The moving leaves and branches of oak, elm and beech all filled her with sudden and constant fear. She fled this way and that, up hill and down, taking strange detours because in each shadow on the hills or in the glens she was fearful of finding Rinaldo—terrified that, for all she knew, he might be right behind her.

She fled like a fawn that has just seen a leopard catch its mother by the throat and tear her open, and so flies in panic from grove to grove, feeling the brush of each broken branch as the pitiless teeth of the beast of prey.

All that day and night and half the next day she went on, wandering, not knowing where.

She found herself at last in a grove like a garden, lightly stirred by a benign breeze-like a garden, or even a brilliantly decorated chamber. Two clear streams murmured through, pausing to keep it all fresh and green and making sweet, low music over the pebbles in their beds. Here Angelica felt safe at last, as if she were a thousand miles away from Rinaldo. She was exhausted by fear, flight and the summer's heat, and she told herself she had better rest a while. Dismounting among the flowers, she let the palfrey loose; he went wandering down to the edge of the bright water, where the grass was best. Not far away, Angelica herself came upon a delicious thicket of blooming thorn bushes and red roses beside the mirroring pool. Tall, full oaks shaded it on either side from the hot sun. A hollow in the heart of the thicket made a cool, well-hidden room, with leaves and branches so thick and interlaced that neither the sunlight nor inquisitive eyes could penetrate it. And inside, the short, soft grass made an inviting bed.

The harassed beauty lay down and immediately fell asleep. But not for long; she was soon awakened by the trampling of approaching hoofs. Then there was silence again. Getting up quietly, she peeped out, and saw that a knight in armor had come to the edge of the water.

She did not know whether he was friend or enemy.

Fear and hope tore her heart and left her too weak to move. She waited and did not break the stillness of the place with so much as a sigh.

The knight sat down at the very edge of the water and rested his chin on his hands. He remained so lost in thought for so long that he seemed to have been turned into insensible stone. For more than an hour, he stayed there, silent and sad. Then he began to lament so softly that the sound would have melted granite with pity, have tamed the wildest tiger. He sighed and wept so profusely that his cheeks resembled rivers, his chest an Etna.

"The thought," he said, "the very thought freezes and burns my heart and gnaws at it so painfully. What can I do, when I have come too late, and someone else has had all the rich spoils—everything! And if I cannot touch the fruit or flower, why do I, why must I, go on torturing my heart for her?

"A virgin is like a rose, alone and safe in the midst of its own thorns in a fair garden. The soft, gentle breeze and the dewy morning air, the water and the earth yield everything to its favor. Neither shepherd nor flock comes near. Longing youths and maids in love want to wear it.

"But no sooner is it picked from its green stem than it loses all the favor it had of men and of Heaven, and grace and beauty—all lost. The virgin who gives away the rose, which she should value more than her sight—or her life-loses the value she had in all her other lovers' hearts. She is worth nothing to them, to anyone except the one she generously allowed—take the rose. . . . Oh, cruel Fortune! ungrateful Fortune!

Others triumph and I die of desire! But can I stop wanting her? Can I lose my life itself? Ah, sooner-today!—were my days ended, than I live any longer, if I am obliged not to love her!"

In case anyone is beginning to wonder who this man was, shedding all those tears in the brook, he was the King of Circassia, Sacripante, tormented by love. I should add that love was the sole reason for all his anguish, and that the object of his devotion was Angelica.

She knew his voice very well.

For love of her, Sacripante had journeyed from where the sun rises to where it sets. He had learned, in India, bow she had sailed for the West with Orlando, and he had followed. Then in France he learned that the Emperor had sequestered her, in order to give her to the nephew—Orlando or Rinaldo—who gave the gold lilies of France most help that day against the Moors. He had been in the field and knew of the cruel rout Charlemagne suffered. He had looked for some trace of the fair Angelica but had been unable to find any. This, then, was the new sorrow that made him lament with words so pitiful that they might have slowed the sinking sun that afternoon.

While he suffered and cried and said a lot of other things that I do not care to repeat, his good fortune brought everything to Angelica's ears. And she paid close attention to his moaning complaint, his look of misery—all because his love for her never slept and gave him no rest. This was not the first time she had heard such things, and not the first time she had heard them from him. But being colder than a marble column, she did not condescend to pity him, or any other man, save for that one time she had loved Rinaldo, before he loved her. She behaved with contempt for everyone; no one in all the world was deemed worthy of her love.

Now, however, lost as she was in the woods, the reunion did not displease her, and she decided she would accept Sacripante as a guide. (A drowning man is proud indeed if he will not ask for help.) She reasoned that if she let this chance go by, she would never again find an escort so reliable. She already knew by long trial—when she was besieged for her beauty in her capital, Albracca—that this king was more constant than any of her other suitors. Not that she intended to ease the pain that consumed him, or compensate his old wounds by giving him the pleasure every lover longs for. Instead, she planned some pretense, some fraud, to keep him dangling just long enough to serve her purpose, when she would once again assume her usual coldness. Out of the dark, hidden thicket of thorns she stepped—with a display of beauty stunning as if Diana or Venus had suddenly shown herself in the dark wood.

And "Peace be with you," she said to him, "and 'may God preserve my good reputation and not allow—against all reason, whatever you may have heard about me—that you hold so false an opinion of my honor."

A mother would not raise her eyes to a son lost and believed dead in battle with more joy and wonder than this Saracen felt when she appeared to him so suddenly, in all her pride and grace and angelic beauty.

Full of sweet desire, he moved to her, his lady, his goddess, and she threw her arms around his neck and held him tight for a moment. She had never gone so far when he was fighting for her in Albracca, in Cathay.

Now she saw in him the sudden promise of seeing her own land again, and soon.

And she gave him a complete account of events from the day she had sent him to request aid for Albracca from the King of Sericana and Nabatea. She told him how Orlando had kept her from death, dishonor and all evil, and how her virgin flower was preserved, untouched as in her mother's womb.

Maybe this was true—if not believable to a man in his full senses. But it was easy for Sacripante to believe it; he had lost his way in a deeper error-love.

Love can make what a man sees invisible to him, and Love can make him see things that are in truth invisible.

Sacripante believed her because he wanted to. And it was true enough that she did not love Orlando. She did not tell Sacripante—any more than she had told Orlando—that she had come back to France only in order to find Rinaldo. That, anyway, no longer mattered, because she had drunk from the Fountain of Disdain in the Ardennes wood.

Sacripante, believing her, was meanwhile saying to himself, "If Orlando—the idiot—did not know enough to seize his good fortune, the loss is his. Fortune may smile but once. I will not follow his bad example. I will not let go the chance that is given me, and then be sorry for myself again. I shall pluck the rose—fresh, in the morning—for if I leave it any longer I may lose it—overripe, overblown. I know very well that you can't do anything with a woman more sweet and pleasing to her, however scornful she may pretend to be about it before, however sad she may be afterwards, for a while. I am going to pluck the rose, and I will not be put off by any pretense or protest."

But while he planned and prepared the sweet assault on Angelica, who did not suspect it, they heard a great noise from the nearby woods. Most unwillingly, he angrily gave up the plan, put on his helmet, went to his destrier, bridled him, mounted and took up his lance.

Out of the wood rode a knight who seemed strong and brave. His surcoat was white as snow, and a pure white streamer flew from the crest of his helmet-showing, Sacripante thought, that he was newly knighted. The king could not tolerate this interruption of his pleasure. He confronted the unknown knight with an evil—or guilty-look, and challenged him to fight, sure of his own ability to knock him out of the saddle.

The knight cut short Sacripante's threats, spurring at once and lowering his lance to the rest. Sacripante wheeled about in a rage and they rushed with leveled lances straight at each other.

Fighting lions or bulls do not leap at each other so fiercely as these two warriors rode. Each spear passed through the opposing shield. The encounter made the woods resound, from the grassy dale where they met to the rocky hilltops on either side, and it was good that both their breastplates held behind their pierced shields. Neither steed shied, either. They butted like rams. Sacripante's did not survive the blow, but died almost immediately. The other horse also fell, but was quickly revived by the spurs in his sides, while Sacripante's remained lying on its master with all its dead weight.

The unknown champion, upright and seeing the other on the ground under his horse, decided he had had enough of that combat and did not care to renew it.

He rode away at full speed through the trees; and before Sacripante had freed himself (with Angelica's help) the white knight was almost a mile away.

Like a stunned and stupefied ploughman after a thunderbolt has just knocked him flat, climbing to his feet, seeing his cattle dead all around him, and trees without their green crowns—so Sacripante got up after his fall. He especially regretted Angelica's being there to see the unfortunate accident. He sighed and moaned, not on account of bruises, dislocations or fractures, but purely on account of shame-shame greater than any he had ever felt before or would again. Moreover, besides being overthrown, his lady had had to help him get out from under his expensive dead horse. He would have remained speechless forever, I think, if she had not helped him in that, too, and given him his voice again.

"Oh, my lord," she said, "don't be too sorry about this! Because the fall wasn't your fault, after all, but the horse's. He needed rest and refreshment, not jousting.

And that other knight has not added to his own glory. He was the loser, because he did not wait. That proves it. If I know anything about these things, I know that whoever first quits the field is the loser."

While she was comforting him, a messenger with horn and pouch galloped up, looking tense and tired, on a worn-out horse. When he reached them, he asked Sacripante if he had seen a warrior with a white shield and streamer pass by.

"As you see," said Sacripante, "he has just overthrown me, and he went that way, just now; and so that I shall know again whomever it was who unhorsed me, let me know his name."

"What you ask me," the messenger told him, "I will answer immediately. Know, then, that you were knocked from your saddle by the noble valor of no man, but by that of a gentle damsel. She is brave, and even more fair than brave. Neither do I hide from you her famous name: it was Bradamante, the daughter of Duke Aimone, Rinaldo's sister, who has taken away from you, sir, whatever glory you may have earned in this world."

With which, he loosed the reins, spurred and rode on, leaving the Saracen unamused, not knowing what to say or do, burning with humiliation. He could not bear it—not only felled, but felled by a woman! Mounting Angelica's poor palfrey, he pulled her up behind him without a word—postponing more pleasant pastimes for a more peaceful place.

They had not gone two miles before they heard the surrounding woods in another uproar, and soon a great destrier appeared—richly adorned, equipped with gold, but riderless and leaping or crashing through everything in his way.

"If the gloom and all these tangled branches don't deceive me," said the lady, "that horse ploughing through the middle of the forest where there is no path is Baiardo—I'm sure it is Baiardo. I know him.

Oh, how well he sees what we need! He's coming to me! He' knows that one spent horse is not enough for the two of us, and he is coming to help."

Sacripante of Circassia dismounted and approached Baiardo, intending to take the reins in his hand. Baiardo responded by turning and kicking like lightning, but the blow did not hit Sacripante. Unhappy the man who feels those hoofs—for Baiardo could kick hard enough to crack a great mass of metal, a metal hill, not just metal armor.

Then the great beast went tamely to Angelica, as happy as a dog greeting a master who has been away for days. Baiardo still remembered how she had served him with her own hands in Albracca—the time when she was in love with his master Rinaldo, when Rinaldo was so cruel and ungrateful to her. She took the bridle with her left hand, and stroked his neck and his chest with the other. The steed—who had extraordinary intelligencequieted down like a lamb.

Sacripante seized the opportune moment; he mounted Baiardo and held on tight. The damsel returned to her own poor palfrey.

Then, turning, she saw that tireless knight who walked, resounding in his armor, through the wood behind Baiardo—after Baiardo, and after her. All her new hatred took fire again when she recognized Rinaldo.

He now loved and desired her more than life; she hated him and fled like a dove from a falcon. There had been a time when he bated her more than death and she loved and desired him; chance had now changed their roles.

For this love and hate was caused by two springs of water of different effect not far from each other in the forest of Ardennes. One fills the heart with love.

Whoever drinks from the other one is left without love—all ardor turned to ice. The one was a natural spring; the other, a fountain made by Merlin for lovers in anguish. Rinaldo had drunk deep from the one, and coming upon Angelica as she returned from the East, had on the instant been melted by love of her. But she in that moment was just drinking from the other, fear. Her clear eyes darkened, and with trembling voice and tormented expression she implored Sacripante not to wait for the approaching knight but to escape with her. "Am I then," asked the Saracen, "am I then so discredited in your eyes that you consider me useless? Not good enough to defend you from that fellow? Have you already forgotten the battles of Albracca? And the night when I, alone and naked against Agricane and all his host, shielded and saved you?" She did not answer. She had no answer. Rinaldo was by this time too close, already threatening the Saracen, as he saw the horse—his own, indeed—and the lady whom he proposed to make his own. What happened next between these two proud knights, I reserve for the next chapter.

Please let us know in the comments if you like this story. If there is enough interest, we will publish more of this story.

Two of Mr. Fox’s 156 eBooks have been turned into audiobooks narrated using cutting-edge AI narration technology. The Books can be found on Audile. The Borgia Blade and Madame Buccaneer are available now. [Please note: All links to Amazon are Affiliate Links.]