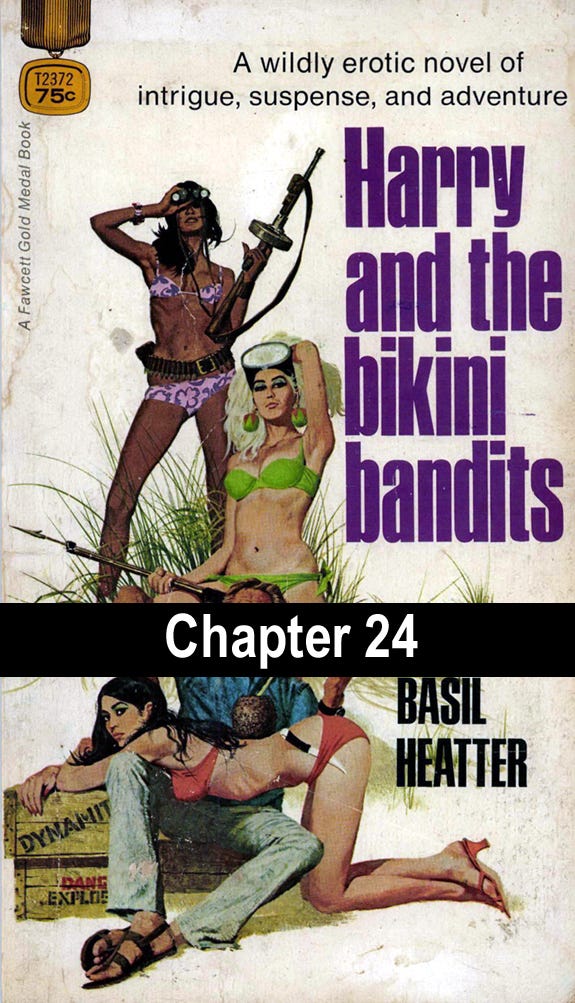

Harry and the Bikini Bandits by Basil Heatter - Chapter 24

1971 Genre: Vintage Sleaze / Casino Heist

A wildly erotic novel of intrigue, suspense, and adventure...

There's a lot to be said for my Uncle Harry. Mostly unprintable. All my life I'd heard about him, and from a distance he was a kind of legend. But the moment I signed on as one-man crew to his beat-up old bucket, Jezebel, I found my hero of the sea was really a pirate. Broads and booze kept him afloat between capers—and so far, his luck was holding...

But this new harebrained scheme—to heist the loot from an island gambling casino—was the daffiest—and most dangerous yet.

And there I was. Right in the middle. Up to my virginal ears in naked nymphs and Nitrous oxide—with nothing between me and the future but a leaky getaway and a pot of gold that was fast disappearing behind Harry's private rainbow.

CHAPTER 24

At midnight a light went on in the house on the hill. At first I thought it was a star, but it was too yellow for that and it flickered the way a kerosene light will. I had been sleeping and it was just luck that I saw the light. It was on for about ten minutes and then went out. At least I knew I was not alone on the island.

I wanted to start up the hill right then, but it would be a bad time to come crunching in on somebody. In addition, there was no moon. Even if there was a road, I could not have found it. So I sat there and shivered and dozed through the rest of the night.

I was up at first light and climbing the hill. The house was further away than I had thought, and I was glad I had not attempted it at night. The road soon petered out to nothing more than a track. I was very thirsty. Wild orchids bloomed along the way. Far below I could see the surf beating on the reefs.

The house had looked imposing from a distance, but as I approached I could see that it was rundown and the windows were broken. It was hard to believe anybody really lived there, but I was sure I had seen a light. Then I saw a couple of chickens and I knew that chickens did not grow wild.

The door hung crazily from broken hinges. I banged on it a couple of times and heard movement inside, and then a very old black man came to meet me. He wore nothing but a pair of dungarees, and his body was covered with white fuzz. He was bent over with age, but his shoulders and arms were still immense. He said nothing, only stared at me in amazement. I asked if I could have a drink of water, and he pointed to a tin dipper hanging from the side of a well at the corner of the house. I let down the bucket and brought up some water that did not look too healthy. Since it was obviously the only source of water in the place, I could not afford to be too particular. I gestured toward him with the dipper but he shook his head. I was beginning to wonder if maybe he was a deaf mute.

Then he spoke in a voice that rumbled out of his chest like the roll of drums. "I am Gideon Albury."

"Glad to know you, Mr. Albury. I'm Clay Bullmore."

"What is your purpose here on Highborne Cay?" That was the way he spoke, like some Shakespearean actor but with the soft Bahamian accent that is almost like music.

"Well I'm just looking around."

He seemed to find that an acceptable answer and nodded without comment.

"You haven't seen a blue thirty-five-foot ketch named Jezebel, have you?"

"It would be most difficult to make out the name of a passing vessel from here."

I could see what he meant. From up there on the hill the sea spread out on both sides like a great flat sheet of metal and to the southeast I could see a whole chain of islands. Many miles off to the west I could make out the grayish wedge of sail that marked a passing Bahamian sloop.

"How did you arrive?" said the old man.

"I came in on the mailboat yesterday afternoon."

"Are you alone?"

"Yes."

"To be alone at your age is difficult. At mine it is a pleasure. Come into the house, Mr. Bullmore."

There was nothing much inside. An old bed, one chair, a cooking pot, some dishes. And books. This old man was a great reader. No radio. Obviously no fear that he might know anything about the casino. Anyway he wasn't nosy. Asked me no questions about myself. Just talked nicely and quietly about the Exumas, the changes in the weather, fishing, his two chickens, the land developers who had tried to chop up his island into building lots and had gone broke, people on the neighborings cays, an American woman named Hester Soames on Rumbullion Cay, and so forth.

I said, "I'm looking for this boat . . . "

He nodded, his bright old eyes searching mine.

"My uncle is on it and we got separated somehow and I think he's in this general area. Maybe there is a skiff or something that I could use to take a look around some of the cays.

"I have a skiff," he said. "A little sailing skiff."

"Could you take me around? Could I rent your boat for a few days?"

"Rent?"

"Well, you know, pay you whatever you think it's worth. I don't have any money with me right now but I have this watch . . . " I unstrapped Mr. Burger's gold watch and held it out to Albury. He examined it carefully and said, "A beautiful timepiece."

"I know."

"Too expensive to be exchanged for the use of my little skiff. And furthermore I have no use for a watch here. I go to bed with the sun. In any case, have I asked you for money?"

"No, but . . . "

"You will be my guest, Mr. Bullmore."

He was very courteous. A really beautiful old man. I wondered where he had come from with his books and fine manners and what he was doing living there alone, but I thought it better not to ask. I was beginning to appreciate the fact that there were people who did not ask me questions, and I thought it only right to return the favor. He gave me some biscuits and cheese and coffee. Although he urged me to take more I refused, since I could see that he was obviously short of supplies. He watched me eat, but ate only a couple of biscuits himself. When I had finished he said, "We can start looking for your boat now, if you like."

"That would be fine, sir."

He had me doing it too. He had such immense dignity and beautiful manners, that old man, that he soon had me talking like some character out of an old English movie.

He led the way down a path through the brush between all sorts of flowering things and clouds of big white butterflies. Back in there we were sheltered from the sea breeze and the sun was murderously hot.

"You should be wearing a hat, Mr. Bullmore," he said. "I know. I left it on my uncle's boat."

"Perhaps we can find you something in the skiff." The skiff was typically Bahamian—unpainted, crudely built out of native woods and obviously very strong. It was moored in a small lagoon at the base of the hill. We waded out to it and climbed over the gunwale. The old man dug around among some rope and other junk in the forward part and found an old straw hat for me. It was a little too big, so he tied a piece of twine over the top and then under my chin.

Mr. Albury got up the tattered, baggy old sails and tacked out of the lagoon against the incoming tide. He did it all so easily and beautifully that you had to think twice about it to realize how much skill was involved. Considering the kind of equipment they have, all the Bahamians are tremendous sailors. By rights those tubby, old, shoal draft boats with their sloppy rigs should not sail at all, but somehow they do. I should think it would give most of the high-powered modern yacht designers an awful pain in the neck just to see one go by.

When we had cleared the lagoon, he explained the situation to me. There were any number of islands ahead of us stretching southeast for more than a hundred and fifty miles. Unless we wanted to spend a year or two at it, we could not search them all. Since I had mentioned Wardrick Wells and Galliot Cay, which lay about twelve miles southeast, we could start off in that direction and see what turned up. I said I hated to be such a bother to him, and he said he had been looking forward to a cruise anyway. He had not been down to see his friend Miss Hester in a long time, and it would be a good opportunity for a little visit.

The islands were blue and hazy in the distance and the water was unbelievably clear, shading off from a sort of milky color over the flats to light green and then dark blue in the channels. It was the most beautiful place I had ever seen. Back up on the hill Mr. Albury's house was no bigger than a white dot.

The little sloop moved along at a steady pace and by twelve o'clock we were halfway to Rumbullion Cay. Mr. Albury gave me two biscuits and half a cup of water from a wooden cask. He took nothing for himself. Rumbullion Cay began to shape up in the distance. I could see a low, flat-roofed house on the point facing toward us. Mr. Albury said that if there were any strange boats in the area Miss Hester would probably know about them. She lived alone on the island and from her point she would see almost any vessel taking the inside passage north or south. Of course, Harry might have gone by in the dark—if in fact he had come this way at all—but Mr. Albury said it would certainly be worthwhile to stop to talk to Miss Hester, and I agreed.

There were reefs all around the island, but Mr. Albury never hesitated. He ran straight in over them as if they didn't exist. We touched once, but the stoutly built old boat bounced right across. I was learning that this was the Bahamian method of navigation. In those shallow keel boats you could get away with it. Any modern, yachty craft would have been wrecked instantly.

Mr. Albury said there was an anchorage around the other side of the island. We would go in there and walk back to the house. I could see the house more plainly now, and it was quite different from anything else I had seen in that part of the world. It was very simple and very modern with lots of glass and unpainted wood. There were two people sitting out on a sort of terrace on the west side away from the wind. We were still some distance away and I could barely make them out.

"Miss Hester has a guest," Albury said. "I'm surprised. She never has anyone here."

The woman stood up. She appeared very small. She waved in our direction and Albury waved back. The man remained seated. As we approached I could see that he had black hair and a black beard, but that the rest of his body was covered with red hair. It was Harry.