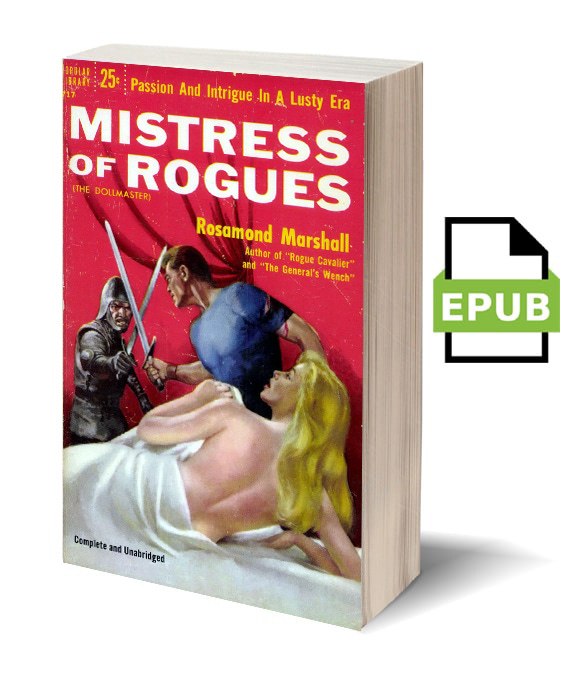

Chapter 16 - Mistress of Rogues by Rosamond Marshall

1954 Genre: Historical Fiction / Racy Romance

WEAPONS OF LOVE

In flight from her brutal husband, blonde Bianca fell into the hands of the puppeteer, Belcaro. She soon learned he wanted her as bait, to snare the most profligate princes of the Renaissance.

In exchange for power, Belcaro passed her from rogue to rogue. Until the night he found he could not resist the ravishing courtesan he had created.

But by that time Bianca knew him for the monster he was. And she was ready and waiting—with all the weapons of her amorous career!

"Miss Marshall's novel concerns the downfall of a lady ... whose golden hair and other charms were reminiscent of Botticelli's Venus... Bianca had a good many men in her life." —NEW YORK TIMES

You can download the whole story for FREE from the Fox Library. This is a limited-time offer!

CHAPTER 16

Two Mendicants roamed the streets of Florence asking alms and bedding at night under the loggias. Sister Carita and her friend Nello.

The winter is a cruel season for the poor—so cruel that the flame of a few sticks can be a blessing and a sup of gruel a banquet. I would not have had it any other way.

"Thou couldst seek refuge in some convent, Bianca," said Nello when he saw my weariness.

"How would I find the children if I were behind con vent walls?”

"The children ... always the children!" grumbled the little man.

"Good Nello! Seek thou refuge and an easier life in some rich house! The Magnificent himself would be glad to have thee for his jester."

"The children might not know thee, Bianchissima," Nello answered fretfully, "Me they would recognize ... quick as that!” He snapped his fingers.

Dear, crusty little fellow.

I never ceased to wonder how three hundred and ninety-nine children could have vanished into thin air. Fra Angelo? Sister Martha of the loudmouth? How could she have been silenced?

I questioned shopkeepers, street vendors and carters, itinerant monks, farmers and market women. I questioned the toll men at the city gates and the bargemen on the Arno. "Did you see a troop of children traveling in company of a Mendicant Friar and some White Sisters?” I questioned gravediggers and carriers of the dead. "Did you remove any dead children from the palace in Via Michelozzi?” The answer was always "No."

Whither had they gone?

Ofttimes when we wandered in the neighborhood of the palace and saw lights shining in the great pile that had been my home, Nello would mutter, Let me take care of Belotti!”

"No, Nello!”

“Then let me go see what I can find? Perhaps his stolen gold? Some jewels?”

"No, Nello.”

I dared not tell the little man my fears that discovering the wife of his long-time master in Florence, the scoundrel might seek to destroy her. Belotti must have suspected that the Doll-master had met with foul play. When Belcaro did not return to Florence would not the Doll-master's trusted steward have hastened to Monte Speranza to seek his master?

Nello had boasted about his victims, "I buried 'em so deep not even the trump o' doom could get 'em up." But an observing eye might find the graves and dig up the bodies of the hunchback and his deaf-mutes. Even the mortal remains of Beppo, of Sisters Beata and Ursula might have been found. Undisturbed in his wicked com fort, Belotti believed himself safe from all harm. But knowing that I might point the finger and cry, “Thief!" he'd never rest until my lips were silenced. Therefore, I steered a wide course from Via Michelozzi.

Find the children—and hide the Book in a safe place. This was the burden of my care. My only joy in these dark days was to slip into some humble parish church and make my devotions. I avoided the temples where the rich worshiped and knelt at the shrines of the poor. Day after day I prayed for Andrea and Fra Giacomo. I prayed also for “my” children and that Heaven might direct me to them.

There is power in prayer! Nello and I were wandering one afternoon in the Via Calzaioli, the stock-maker's street, so called because here were the famed manufacturers of the Florentine serge stockings preferred and worn all over Europe.

This street had a tongue that spoke of master painters and sculptors like Donatello and Michelozzo. Here Guelf and Ghibelline had engaged in fratricidal warfare. Here the Madonna received gifts of flowers, fruit and gold on Ascension Day.

I lifted my tired eyes to Or San Michele, where in olden times provident rulers stored grain against winter famine. Generations of grateful Florentines had made it into a shrine. Whilst I daydreamed, Nello's eyes were on a bakeshop—the name Widow Tentari over the door.

"I have three coppers. Come! I'll buy some fresh bread." I waited at the door while Nello went in.

The shop in Via Calzaioli was a small part of the bakery. I could see through the flour-dusted windowpane a vast bakery, the red glow of oven fires. Men with whited faces kneaded the dough with strong arms or plied long-handled bread shovels.

Nello came out with a wide grin on his homely face. “Come, Bianca! Come to the alley behind the bakery! The widow Tentari gives bread away!" He took my hand and hurried me through a narrow way between two leaning houses and we joined the line of beggars who were shuffling forward step by step.

A fresh-faced woman of middle age stood between two great basketfuls of bread and placed a loaf in each outstretched hand with the gentle greeting, "For Annetta's sake.”

"Who is Annetta?” I asked of the crone ahead of Nello and me.

"The widow Tentari's little daughter. She was taken by the plague. The mother remembers her each day with the giving of bread and it makes her very happy when there are children in the bread line."

I could not help smiling at the specious remark—"it makes her very happy when there are children in the bread line." Why did widow Tentari not labor to save children from beggarhood?

When Nello and I accepted our loaves with thanks, I stood aside and waited until the baskets were empty.

The widow Tentari, warmly dressed in black velvet and wearing a fine golden locket and chain turned to me. "I'm sorry, poor woman! My bread is all gone. Come back tomorrow.”

"We will, good lady! We will!” said Nello who already had his teeth in the loaf.

"I too have lost children," I murmured. “All three hundred and ninety-nine of them.”

"Three hundred and ninety-nine?” exclaimed the

widow.

"It was an orphanage. I am ... or was ... their keeper."

"She was rich!” piped up Nello with a full mouth. I pinched him. “Rich in duties and service.”

The widow regarded us with a somewhat suspicious eye. “Three hundred and ninety-nine children? Art thou a member of some religious order?"

"Only a humble servant of charity, my lady."

My words and manner seemed to quiet her suspicions. "Many children come to my door. Some days I have counted seven ... eight ... even a dozen. Thy wards could be among them."

I thanked her again in leave—taking and every day thereafter, I returned to the alley where the widow Tentari waited with her bread baskets. Nello was happy! He could eat his fill, but I sometimes forgot to take my loaf for peering into pinched little faces. This one? That one yonder? Alas! None were the survivors of Siena.

When Nello understood the reason for my interest in the beggar children he proposed to tumble and perform his acrobatic tricks. "Our children would be sure to remember Nello!”

Bless him! One day his efforts were rewarded when two tattered waifs broke out of the bread line crying, "Nello! Nello!”

They were ours! Little Gino and his sister Lisetta.

I led them aside, fed them and plied them with questions. “Where are thy playmates? The good Sister Mar tha? Fra Angelo?”

All they could remember was that a “bad man” had chased them into the streets. They had "got lost.”

“These are two of my orphanage," said I, leading my finds to the widow Tentari. “Gino and Lisetta are their names. Thou wouldst not believe it ... Lisetta's hair is as blonde as ripe wheat on the stalk when it is clean."

"Wait!” said the widow Tentari. "I'll finish handing out the bread and then speak with thee.”

It seemed to me that the gentle voice of Jesus spoke when she said, “I have a cellar. It is warm and dry. I can spare a brazier and blankets. Take these two sparrows in side. I'll send hot water and soap and a bale of straw for bedding."

It was a new beginning! As a magnet attracts iron filings so Lisetta and Gino drew other children. We soon recovered twenty of our Sienese orphans—and Sister Mar tha who brought in sixteen more. What a tale she had to tell!

"We were routed out of our beds in the middle of the night by Belotti who herded us into the streets and threatened us with beatings if we did not go away from Florence. I took about two dozen children with me and struck out for Perugia. Sister Veronica had another dozen. Sisters Agata and Tommasa went one way and Fra Angelo the other. My brood did not go far. Some died of the cold. Some strayed away. I brought only sixteen back to Florence and we've been begging ever since.”

I was faced with another dilemma—how to care for the children?

"The widow Tentari is rich," said Nello with a wink.

"She owns three houses in this street ... they are empty. Make a sad voice and say, 'Good lady, give us a house for the children.'"

Beg for my wards? Of course I'd beg.

The widow tweaked her nose and scratched her chin. “Thirty-six children?”

“Yes, my lady.”

"I have a small house ... the roof is poor. The windows are broken..."

"Roof and windows can be mended, good lady.”

"Oh! Very well,” she said. "Take the house. It is four doors down the street ... a dove in bronze for the knocker.”

I christened our new abode, “House of the Dove." Broken windows? Leaky roof? 'Twas a palace for us who had known the torture of nights in the open. We mended, patched, swept and scoured. Ere the first snows fell we were snug and warm. Scarcely a day passed that some orphaned child did not pull our latch string. We made it extra long so that the littlest of them could reach it!

Drawn to blonde Lisetta, the widow Tentari opened her purse even wider. We had shoes for the children. We had cots and warm blankets. All she asked in return was that Lisetta visit her, sup with her, play with little Annetta's dolls. Our number increasing, she opened a second house for our use and then a third. When March winds blew, we counted three hundred children at our board and six more repentant women workers had joined forces with Sister Martha and me.

In this sweet moment of fulfillment and peace, my thoughts turned more and more often to the Book. I kept it wrapped in a plain white cloth and hid under my straw mattress at the foot of my bed. But I was far from tranquil. Would I ever find a safe repository for this most sacred tome?

Each night when the House of the Dove was quiet the little ones dreaming, Sister Martha snoring, Nello safe in his little room under the eaves—I closed my door, brought out the Book and studied it with reverence and joy.

What good tidings Paul gave to the people of Corinth.

Be perfect, be of good comfort, be of one mind, live in peace; and the God of love and peace shall be with you. And again Paul said,

Charity suffereth long, and is kind; charity envieth not; charity vaunteth not itself, is not puffed up, doth not behave itself unseemly, seeketh not her own, is not easily provoked, thinketh no evil; rejoiceth not in iniquity but rejoiceth in the truth.

All truth was contained between the parchment covers of this Holy Book.

I shall remember that dreadful night until I die! It was clear and cold, the stars so bright in the heavens that they seemed very close. I prayed. When I reached under the mattress to take out the Book, my hand touched emptiness! The Book was gone! I could not believe it! Stripping back the mattress I searched again. IT WAS GONE!

I 'ran upstairs to Nello's attic to question him.

"I haven't seen the old book since we moved into the House of the Dove," said he. Then seeing my frightened face, he tried to reassure me. "I'll find it, Bianchissima. Do not fear. I'll find it."

I cautioned him. “Nobody must know the Book is valuable ... So valuable that our lives might be forfeit if it were found in our possession. Say ... it is my breviary."

I went from bed to bed waking the children. "Some little busy-body took Sister Carita's breviary. I want it back.”

Sleepy eyes blinked at me.

"Speak up!” said I. “I will not punish, but I want my breviary."

By now Sister Martha had awakened. "Breviary? We'll search for it in the morning, Sister Carita.”

I spent the night on my knees in prayer.

Next morning at breakfast—a hundred pairs of eyes staring at me I made a stronger plea. "Bring back Sister Carita's breviary and I will reward the good little girl or boy with a gift."

Not one child answered!

"Come, come, playmates!" piped up Nello. "Bring back the breviary and I will show you such clowning as you have never seen before.”

The children clapped their hands and shouted, "Nello! Nello! Make the clown!” But not a word was said about the Book.

“Let me tan their bottoms one by one!" whispered Sister Martha in my ear.

"No," I answered. “We'll watch them."

All day we two women and Nello played a cat—and mouse game with the children. Which one was the culprit? Where had he or she hidden the Book? We searched the house from attic to cellar and found—pieces of glass, a bent nail, a wooden dolly dressed in a rag-treasures of children whose toys were salvaged from the rubbish heap.

The Book was nowhere to be found.

"Nello!" I whispered when darkness fell. "If the Book should fall into the wrong hands, I am of all women, the most miserable."

He looked at me with a strange expression—part curiosity and part compassion. “Has the book something to do with thy love ... Andrea?”

"Yes, Nello. And it also has to do with Fra Giacomo and those poor men whom they would have burned at the stake in Piazza della Signorina."

"A forbidden book, eh?” said Nello with a bird-like twist of his big head.

"Forbidden by narrow-minded, shortsighted men. Hallowed by God and the blood of martyrs."

"Perhaps we too would burn if they found it in our hands,” said Nello with a grimace and a caper.

“It is a risk I must take," I answered. Nello was not the man to let an argument die. “Bianchis sima ... Sister Martha of the loud voice will be sure to shout all up and down the street: 'A precious breviary has been lost.' Would it not be better to tell her to keep her big mouth shut?”

"No!” I cried. “We too know the truth! It is almost one too many."

Nello tweaked his nose. "Not trust Nello? Bianchis sima! I'm surprised. What if I were to find the book all by myself?”

"I'd say ... thou art more astute than ... than all the spies of Florence!” I was still kneeling at my prayers when the bells of Or San Michele struck midnight. The last deep note had hardly died away when I heard a knocking at our door. Taking a candle, I hurried down the stairs to the vestibule and peered through the grating. There stood two armed sbirri, a dirty-faced old man pinioned between them. "What seek ye?”

"Open in the name of the Law!” said one of the sbirri.

I dared not refuse. When I opened the door a man stepped out of the shadows. He was clad in a monk's frock, his face shadowed by the cowl. “Wait here!” he muttered to the sbirri; he stepped in and closed the door. Stabbing a long, white finger at my nun's garb he said, “What is this order, woman?”

“We are Mendicants who keep a home for orphans," I answered with as much calm as I could muster.

"Who is thy bishop?”

“We have no bishop. We worship at Sant'Elmo and Father Benedetto is our confessor.”

The rasping voice was silent for a moment, then my visitor brought an object out of his monk's sleeve and held it out for me to see. "This! The street-cleaner swears he found it in the rubbish heap outside thy door."

I trembled! It was the Book!

"Well ... ?" said my inquisitor. “How did it get upon the rubbish heap? Who is the owner?”

My lips opened to answer, "I never saw it before,” but no sound came. Another instant of silence—I would have been lost! But suddenly a small black-clad. figure hurtled through the casement, scattering glass and lead like shot. The candle went out! I heard a horrid groan and a thump, then after what seemed an eternity—a low moan.

I ran to the kitchen and lighted a taper at the embers of the fire. Returning to the vestibule I saw that the "monk” was lying in a corner doubled up with pain. His cowl had fallen away revealing his features. One of the seven priors who had condemned the printers of the Bible to burn. I helped him to stand.

“Devil!” he gasped, hugging his midriff, "He butted me ... here!" Then he suddenly realized as I did that the Book was gone!

Anger winning over his pain, he rushed to the door and flung it open shouting, "Stop thief! Stop thief!” I heard him give rapid-fire commands. “Search for a small size man in a black mask and cape!” He threw a final word at me—rooted to the threshold. "Hold thy tongue, woman! Speak not of what happened here tonight!”

Reeling from weakness and shock, I leaned against the closed door. The Book was safe! Nello had it! Yes, it was Nello who had burst through the window like a cannon ball!

Soon he came scratching at the alley door. I let him in. "Here!” He thrust the Book into my hands.

"Flee, Nello!” I said as I embraced him. “They saw thou wert of small stature and didst wear a black cloak and mask. Flee or ..."

He would not let me finish. "Hide the book, Bian chissima. They'll come back as soon as it is daylight. I heard the man in the monk's frock give the order. Hide the Book."

"Hide it... where?”

His round eye lifted to a string of pig bladders hung to a beam that Sister Martha used for making meat—and flour puddings—the children's favorite food. Climbing on a stool he cut down one of the bladders, worked it over the Book and tied it at both ends. Then he weighted the packet with an iron and let it down into the bottom of the well in the courtyard.

What better place of concealment? The bladder would keep the Book as dry as a bone.

"I think I'll take a walk," said Nello with a leer and a grin. “They say the winter fair at San Martino is very gay! There are tumblers and jugglers

Nello could fun! I must stay and face the dreaded sbirri of the Priory.

I prayed for guidance—how to prepare my little flock for the coming danger. They knew of the “lost” or purloined book. What would they think when soldiers came searching for a “stolen book," and a “man of small stature” who had stolen it?

I was the more perturbed when in the early morning an eight-year-old named Nina came to me in tears.

“Sister Carita, I must confess. I was helping sweep the dormitory when I saw something under thy mattress. It was a book with pictures. I... I borrowed it .. then, when thou didst speak of a breviary, I was frightened and ..."

“And ...?"

"I ... I stole out into the alley and threw the book on the rubbish pile."

A fatal chain links disaster to disaster. I could imagine the old street-cleaner shoveling our rubbish into his cart and throwing it into the fossa or pit. I could imagine scavengers picking through the refuse. Someone finds the tome, takes it to the Mercato Vecchio and sells it to an old clothes merchant. The old clothes merchant cannot read but he looks at the pictures." Scenes from the Holy Scriptures. A monk ambles by. He calls, “Padre!” From the market to the Priory would be but a step. And so the Priory came to the House of the Dove in Via Calzaioli.

I stared at little Nina 'in dismay. What to do? She'd thought to earn grace by admitting her sin. Make a game of it? Say—“Let Sister Carita's breviary be thy secret and mine." It was the better of two evils.

"Nina ..." I began, but ere I could speak, Sister Martha entered crying, "Soldiers! They ask to search the house."

Nina gave Sister Martha a frightened look and threw herself into my arms, screaming, “I confessed about the Book! Don't let them take me away.”

I clapped my hand over her mouth too late! One of the searchers stood in the doorway. “What's that about a book, little girl?”

Nina's eyes, big with terror, stared at the burly soldier over the gag of my hand. She wrenched herself free and running to the soldier she fell at his feet in a storm of tears. “I took the Book. I took it. But I didn't mean to steal. I was going to put it back.”

"Put it back... where?" "Under Sister Carita's mattress." The soldier eyed me. “Art thou Sister Carita?”

When I assented, he seized my arm with one hand that of Nina with the other and hurried us out to the street.

So great was the Priory's fear that the people of Florence would hear of the existence of even a single copy of Fra Giacomo's Bible—they bundled us into a curtained litter and bore us swiftly to the Bargello. There, in spite of Nina's piteous cries, she was taken one way, I another.

They prodded me up a flight of stone steps. I remember glimpsing a scaffold in the center of a colonnaded court and that a heavy door clanked shut with a sound of iron. The room in which I found myself was not dark or damp or vermin-ridden. Furnished with a bed, a comfort stool behind a screen, ewer and basin, table, chairs and a prayer bench, it looked more like a princely bedchamber than a cell for maldoers—and this was significant to me, for it meant that I was held to be more than a common offender.

A high barred window looked out upon the massive pile of La Badia with its graceful Campanile. I heard the bells calling worshipers to early Mass, and knelt to pray for little Nina. Poor child, what would become of her? She was a high-strung, sensitive child, with more than ordinary understanding.

A gaoler brought me bread and warm milk with honey. I forced myself to take nourishment and it was well I did for the first part of my ordeal was soon to begin.

The same monkish figure that had questioned me in the House of the Dove entered my prison room, sat down and motioned me to a chair opposite. “We know thy true name, Bianca Belcaro," said His Reverence, "and that thou art not of any religious order. We know thou wert in some way concerned with the printing of a forbidden book and that thou didst try to bribe a captain of the Signory in a place called La Certina so that a Friar Giacomo of the Mendicants and one Andrea de Sanctis of Siena might escape justice. We also know that thou didst have in thy possession a copy of this forbidden book. Tell us where it is hid."

I looked into the cold eyes that stared at me noted the thin lips and the narrowed jaw, the out-standing ears, domed forehead and narrow chin. In appearance, this man resembled a bat.

"And if I do not tell?”

“Death would be sweet compared to the tortures thou shalt have to endure."

"I have nothing to say, Reverend Prior," I answered in a low voice.

My questioner's brow bent menacingly. "Speak or we shall put a child named Nina to the rack. She is possessed of a devil that will out when it feels pain.”

"Not Nina!” I gasped. "She is only a child."

"A child in years,” said the Prior. “Adult in sin. She confesses to have stolen the book from under thy mattress. She confesses to have become aware of its wicked nature and thrown it on the rubbish pile. She vows she knows not where it is hid, but she is lying."

"No!” I groaned. “She speaks the truth. I alone know where Fra Giacomo's Bible is hidden."

A gleam brightened the Prior's cold eye. He rose and went away without another word.

Some two hours later guards came and led me down the stairway to the courtyard. Gates of iron opened upon a chamber that smelled of death. There, seated behind a high bench or tribunal—seven men in frock and cowl. In the center of the chamber—the rack, the chains, the irons—all the tools of torture.

I heard a piteous cry.

“Sister Carita!” Nina ran to me. “Do not let them hurt me! I told all I know. I told all! All!"

I hugged Nina to my breast. Her sobs shook me from head to toe. "They shall not hurt thee, little one."

Fear entered my heart as I faced the tribunal, but it was fear for the child caught in this ruthless web. "It is true, sirs. This child knows nothing, nothing beyond what she has confessed. I and I alone am the offender. I proclaim it to Heaven and Earth. I and I alone am guilty.”

"Thy accomplice? The man of small stature, all dressed in black who snatched the book away?” asked one of the judges, leaning across the bench. "Who was he?"

When I stood dumb, the seven muttered among themselves. Then at a sign, the torturers seized Nina and dragged her to the rack. At the same time, my hands were bound to an iron ring set in the wall above my head.

My first thought they cannot torture a child! But the wheels began to turn with a great grinding and squeaking of wood. Hearing Nina scream I gasped one word, "Stop!" —word which brought the machine to a standstill.

"Art thou ready to confess?” asked my questioner.

"Spare the child!" I babbled as fearsome thoughts raced through my mind. Tell the truth? Let them go to the well and bring up the Bible for which Andrea and Fra Giacomo had been willing to die? Denounce Nello who had saved my life? Let the Sisters, the widow Tentari, our confessor, all those who had shared my labors, suffer the consequences of my so-called “crime”?

My questioner struck the bench with his hand. "Art thou ready to speak, woman, or shall we go on with the torture?"

"Not the child!” I cried. "I am the only guilty one.”

I saw through burning tears the torturers lay hold of the wheel and heard Nina's wail of agony. It was enough! "I'll speak!” I cried sagging on my chains. But such is the power of the human frame, I did not faint! "Let her go!" I muttered. "I'll tell all!"

When the torturers loosed the thongs, Nina crumpled to the stones. In a strange silence, one of the torturers laid his ear to her small chest. "She's dead!”

I remember thinking, "She will suffer no more.” Then the word rang clear in my ear. "Hold thy tongue. Die with thy secret unspoken.

When the guards loosened my chains and withdrew, taking the mortal remains of Nina with them, my especial questioner addressed me. “We are ready to receive thy confession."

I faced the bench with head raised. "Sirs, do with me what your inhuman law allows. I am ready to suffer ... and die.”

To my great amazement they did not summon the torturers! No! After conferring in low tones, they had me led back to my cell. Why? Did they fear I would breathe my last as Nina had done? Take the secret of the Book to the grave? I was left alone. No footstep broke the silence outside my prison door until a gaoler brought me food. I touched only the bread and the wine and returned to my devotions.

At sunset I received a second visit from the Prior. This time he spoke gently. "Bianca, we have heard of thy good works ... and that thou didst care for the children of plague-ridden Siena. Reveal to us the whereabouts of the Book and we will let thee return to thy orphans."

I knew by his gleaming eye that confessing or unconfessed, I would never leave the Bargello alive.

The wily. Prior tried all manner of inducements. “Thou didst possess great wealth that is now in the hands of a former steward, Belotti. It is our suspicion that he did trick thee ... with false papers. Speak and thou shalt recover thy properties and thy wealth... to use for charity.”

My unhappy thoughts wandered to the enchanted Villa Belvedere—its lush gardens and the little seaside cove. What a place for our children to play! I remembered the rich fields of Montaldi. I could see Belcaro's Villa Gaia in the ilex grove where Andrea and I had met. Not one I could have many hostels for orphans—and the wealth to maintain them.

"Sir," I answered with a sigh. "I have nought to say."

An angry flush suffused my questioner's countenance. "We shall see!” he muttered.

I lived dreadful hours in waiting. What would be the next move of the Seven? The day waned. I stood at my prison window and gazed out over the city that had been the scene of some of the highest moments of my life. A confused murmur of bells throbbed in the evening air. Beneath my window were the tawny roofs, cloven by the arrow-like Arno and beyond, the dark mass of the woodland Cascine, while around the Bargello tower the swifts were whirling, whirling. I turned from the window and went to my prayer bench.

"Father who art in heaven... show me the way." Mingling with the Paters and the Aves, I seemed to hear Andrea's dying words, “Golden Angel ... take the Book. Spread its message ..." Weeping bitterly, I hid my face in my clasped hands. How, God? How?

Did I sleep or did my senses sink into oblivion? Of a sudden I was roused by the sound of chanting voices. I ran to the window and saw in the square and street beneath a host of lights. An army! Who were these singing, chanting marchers? I strained my eyes and saw—a small, stocky figure gamboling at the head of a vast throng. Those behind were children! They marched in serried ranks. There was not room enough to drop a pebble between them! What were they chanting?

“Sister Carita! Sister Carita! Sister Carita!"

As they came closer to the Bargello, lifting torches and lanterns and tapers on high, I could see their upturned faces, their open mouths.

"Sister Carita! Sister Carita!”

Guards rushed out to stop the invaders. They could not. The crowd—children and elders—pushed them back like a flood that overflows its banks. I heard the tocsin sound—but the chant was louder than the bells.

Here and there among the throng—a yellow hat! The Wolves! Fra Giacomo's friends and my accomplices.

“Sister Carita! Sister Carita!”

That trouble was brewing, not even the Signory could doubt. Here and there quarrelers were exchanging blows. Others were attempting to scale the walls of the Bargello itself.

I saw on the roof of the palace opposite the lithe and daring figure of Gino, chief of the Wolves. He lobbed a fireball across the narrow street onto the platform of the bell-tower. As soon as the flames were extinguished he let fly another flaming missile.

My heart sank. How many would die in a vain attempt to free Sister Carita?

In the face of a catastrophe, I ran to the door of my prison and pounded on it, crying, “Guard! Guard!” at the top of my voice. Was a book, even the holiest of books, so sacrosanct that a thousand must perish to defend it? But even as I uttered my anguished cry, the tumult outside the window ceased.

Anxious to know the cause of the silence, I ran to the window and saw a rider on a white horse pushing his way through the crowds. When the light of a torch illumined his person, I recognized the Gonfalonier.

Had the astute and sensitive Lorenzo harkened to the voice of the people that spoke so loudly out of the mouth of babes?

His daring caught the imagination of the mob. A man's voice was raised. “Viva Il Gonfaloniere!” The cry was picked up by a thousand tongues.

Graciously saluting his subjects, the Prince dismounted and entered the Bargello.

Moments later the door of my prison opened. The Magnificent entered with a page bearing a lantern. “Go, Al dino," said Lorenzo. He turned to me with that slow,

Medicean smile. Giuliano's smile. "Bianca, tonight thy star burns very bright in our Florentine firmament," and pausing he listened to the chant that was again rising from the square like a great bourdon. Then he continued in measured sentences. “I once refused the people who pleaded for the life of a God-touched man. Heaven for bid that I should make the same mistake twice. They want thee free, but the priors want thee ... dead. The bone of contention is the Bible called 'La Certina.' Give it into my keeping, Bianca. Thy safety and the welfare of thy orphans in exchange for the Holy Writ in lingua italiana."

“What assurance have I that the Book will not be consigned to the flames, O Lorenzo?"

"The assurance of a connoisseur of letters and arts."

"Connoisseur who did not hesitate to burn a thousand such books..."

Lorenzo's brow furrowed. “Dear lady, even a prince sometimes has his hands tied. 'In knowledge there is freedom.' There are those who think too much freedom and knowledge would serve the people ill.”

"I heard it said another way, O Magnificent. 'Know the truth and the truth shall make you free.'”

Lorenzo turned his dark, intelligent eye upon me. "Bianca, let me be the keeper of the Book. Safe in my library, it can wait until the time is come' as the Scripture sayeth."

His words brought calm to my troubled breast. Unlike his brother Giuliano, Lorenzo was not a man of changing moods. Hadn't Fra Giacomo called him "a man of open mind”? Reason and expediency ruled him, and he believed in his destiny.

"All thy wealth restored," he argued like an advocate at the bar. "All thy lifetime to spend on good works. The Certina Bible preserved from bigots and fools."

When finding no words to speak, I bowed my head in assent, he took me by the hand and led me to the window.

“Look, Bianca. Look and listen!"

Seeing their Prince and me, the waiting crowds broke into wild cheers. At first the vivas to the Prince were the loudest but soon the chanting, “Sister Carita! Sister Carita!” drowned them out.

"Sic transit gloria ..." murmured Lorenzo. "My bones will crumble under the sign of the palle. My memory … dust. But thine? I think someday thy frail skeleton will lie in a shrine. Chiseled in the marble, not Bianca. Not La Bella Bionda. Not Bianchissima ... not even Sister Carita. The lettering will read, 'Santa Carita.'”

END

Please let us know in the comments if you like this story. If there is enough interest, we will publish more of this story.